“Of all the gin joints, in all the towns, in all the world, she walks into mine.”

Part of what makes Casablanca a perennial classic for the general population alongside the likes of It’s a Wonderful Life and Singin’ in the Rain is that it elicits a sense of unified political sentiment. Despite a primary narrative focus on a contrived melodrama, which sees a wartime folk hero (Paul Henreid) and his wife (Ingrid Bergman) attempt to secure transit papers that are held by a Morocco saloon owner (Humphrey Bogart) who had a passionate fling with the lady while her husband was presumed dead, it sets up a finale in which all of the main players set aside their personal desires in order to serve a greater good, namely defeating the Nazis. I don’t necessarily agree with this reading—perceiving the personal sacrifice of Bogart’s hangdog innkeeper to be the only logical decision he could have made, lest he hate himself and his lover alike—but the prevailing attitude is that these actions are ennobling, and it’s hard to argue against the righteous feeling the climax engenders.

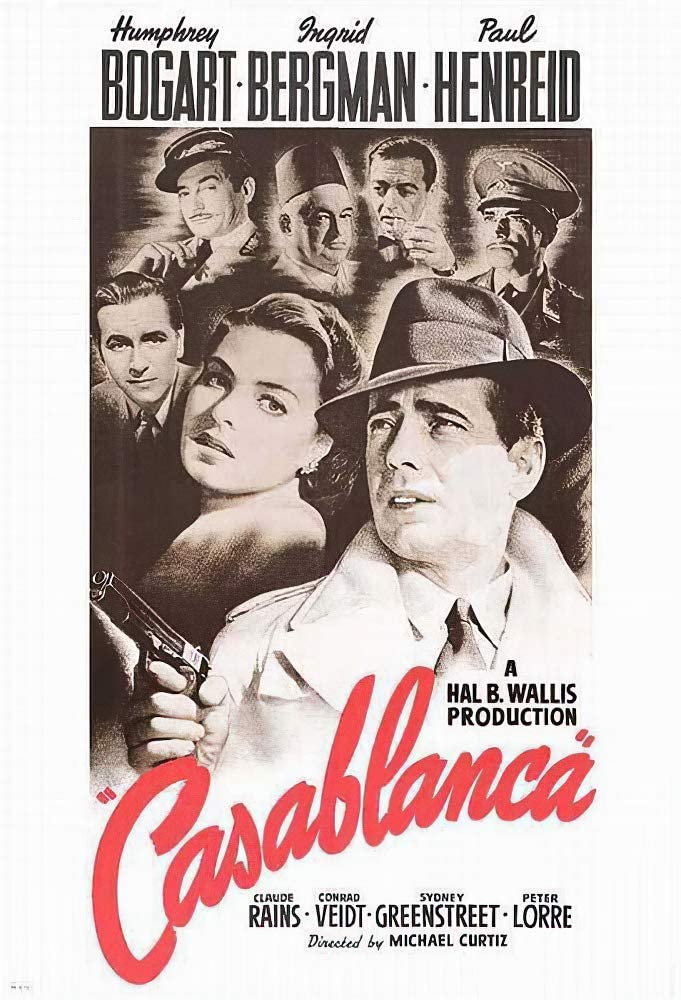

Another reason for its longevity is its presentation. If we take Howard Hawks’ “three great scenes and no bad ones” maxim at face value, then Casablanca passes the test two or three times over. Watching the main trio tangle with one another, along with the likes of Claude Rains, Sydney Greenstreet, Peter Lorre, and Dooley Wilson, trading quips and playing with the expectations of their characters’ archetypes, is purely entertaining. Likewise its abundance of diegetic music, conjured by a variety of instruments and voices, as well as director Michael Curtiz’s senses of rhythm and lighting.

Indeed, though the film has been critically assessed many times over, no amount of analysis can possibly be as gratifying as simply watching it. Which is a backhanded way of saying that its themes of underdog revolutionaries and patriotism vs. personal desire are somewhat insubstantial. Many critics try to whip up something extra, of course—some even try to foist homosexual and Oedipal themes onto it—but ultimately these readings are unnecessary attempts to graft meaning onto a mostly hollow product to justify enjoyment of it. Certainly we must make some allowance for the fact that it was made during the war, and thus doesn’t have the emotional distance of the post-war films that may offer greater insights, but we don’t need to extrapolate something that’s barely there when what is clearly there—top rate cast, enticing atmosphere, expressionist cinematography, memorable dialogue, pleasant rhythm—is sufficiently compelling. A film doesn’t need to be profound to be eminently pleasurable or even to stir up our emotions. It’s similar to the love/hate critique of pure showmanship that must be applied to North by Northwest.

Among the enduring pictures of Classical Hollywood, few seem to stick out so jaggedly from their director’s oeuvre as Casablanca. Curtiz was versatile. He made swashbucklers, noirs, Westerns, horror, biblical dramas, musicals, comedies, you name it. Auteur theorists look for personality, individual style, and recurring themes throughout a director’s entire body of work. Above all, they look for a consistent (if continually evolving) individual vision. Curtiz, operating in such a wide variety of contexts and genres, basically always as a hired gun, suggests only a durable vitality and perhaps traces of a distinctive vocabulary. His career choices position him not as a demanding artist with a personal vision but as a steady workhorse who enjoyed making films. That spirited tenacity marks Casablanca over and above its notable performances, quotable lines, and thematic framework, and offers a bridge between this canonized film and his other work.