“I didn’t mean to sound so cynical, but when I saw all their hopes and dreams in their eyes, I just couldn’t support their illusion.”

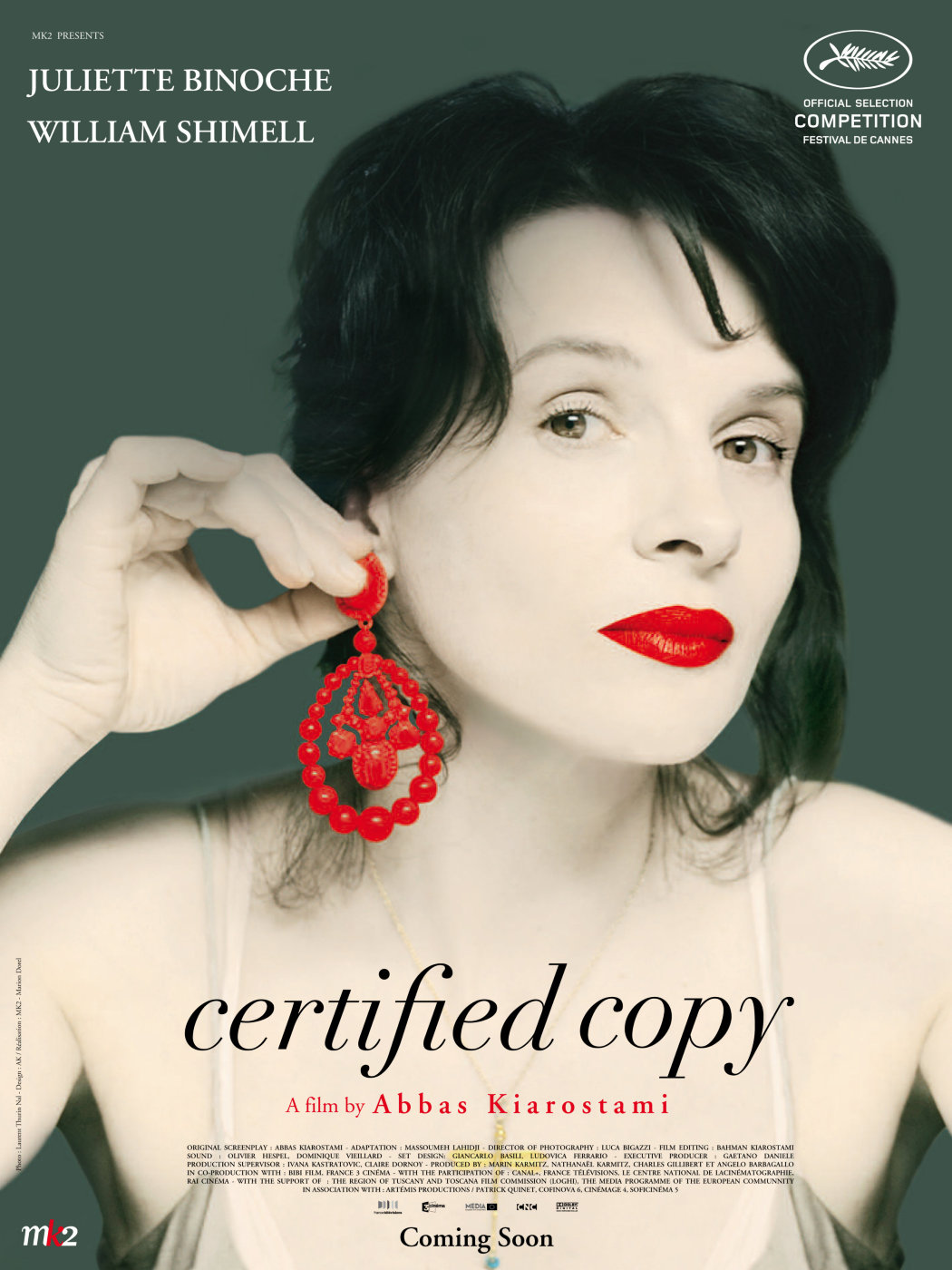

Certified Copy, Abbas Kiarostami’s first film produced outside of his native Iran, is so deceptive in its methods and effective in its artistry that by the time you realize the heady philosophical game it is playing you’ve likely ceded too much ground to reject its supposition without starting the whole thing over and putting on your thinking cap.

Two characters, one a mildly successful scholar (opera singer William Shimell, in his first acting role), the other a small-time dealer of antiques (Juliette Binoche), are introduced to the viewer as strangers. The former is giving a lecture in Tuscany on his new book, which posits that authenticity is an irrelevant characteristic. Even copies are “original” in a certain sense. And genuine articles themselves were certainly derived from some other, still more original specimen. Is the Mona Lisa more or less valuable than the model da Vinci painted? Shouldn’t the value of a thing derive from the response it provokes?

Within the bounds of the film and with nary a whiff of didacticism, this concept is explored to such a degree that the viewer is left questioning the purpose and potentials of storytelling itself.

No sooner have we met these two characters and gleaned the reality of their relationship to one another than that reality begins to subtly shift. The turning point is ambiguous, but before long they’re acting as if they’ve been married for fifteen years—literally, at one point the woman enters a hotel and suggests they stayed there on their honeymoon. In conversations that jump around between English, French, and Italian, they dredge up old arguments, pester about bad habits, reminisce about better days, discuss their son, flirt, ramble.

The film moves along without calling attention to its radical narrative logic—we never comprehend what is driving these changes. The characters rarely stop moving and talking for very long, and the performances in both phases ring equally true. But if we accept the standard framework of narrative storytelling, both of them cannot be true. In which segment are they themselves? In which are they pretending to be other people? But wait—it’s a movie! They are pretending in both instances. Surely, then, if we admit to engaging with the material on an emotional level, we must agree that the facsimile holds its own intrinsic value. If there’s no real truth in art, then the copy of what is true serves the same function. And that’s without any real consideration for Kiarostami’s repetition of images and lines (sometimes from earlier in the film, sometimes from earlier in the director’s career, sometimes from other noteworthy cinematic romances) or his frequent use of reflections, all of which support his thesis.

In an incisive essay excerpted from his book, Mysteries of Cinema, Adrian Martin links the film to the thought of John Cale, namely a line taken from his autobiography that touches on the “unstable reality” of cinema. (His ensuing read on the film through a psychoanalytic lens is quite thought-provoking.) Certified Copy is an extreme example of that notion, conveying a world of awesome instability. And yet, through the power of his craft, Kiarostami is able to shape a reproduction—a thing that the whole film proves to be unreal—into authentic art even as he openly ponders the possibility of such a feat.

Working through the film’s myriad contradictions may lead to different, deeper, or more daunting implications—that there’s no objective reality at all, for instance. It may be true that no underlying reality exists within the context of the film, but I did not sense that it was suggesting its internal, uncertain reality exactly mirrored ours. That is to say, I don’t think Kiarostami is trying to make cynical postmodern points about existence in quite the same way that Antonioni does in films like Blow-Up. Rather, I understand Certified Copy to be a potent, intelligent exploration of cinema’s ability to harness its inherent inauthenticity to connect with the viewer on a deeply human level. It does so, most appropriately, with germane psychological insights. To wit, who hasn’t caught themselves in moments of clarity, seriously considering the vast and secret internal lives of their closest companions? Who hasn’t realized that no matter how well you know a person, they remain to some extent a stranger? Maybe that’s the same as pretending a mime troupe’s imaginary tennis ball is real, but I don’t think that’s the case.