“Obviously you’re telling the truth, for why would you invent such a ridiculous story?”

A friend of mine lent me Charade because he knew I enjoyed Hitchcock’s oeuvre, and while it may be taken as an insult to Brian de Palma, who has spent much of his career in imitation of the great director—Stanley Donen’s film is arguably the best Hitchcock imitation of them all. I mean, holy smokes. This is the guy who directed Singin’ in the Rain and Seven Brides for Seven Brothers… how is it possible that he so skillfully adapts to the thriller genre and to Hitchcock’s style of cheeky, suspenseful storytelling in particular? A woman in trouble, a suave hero, a couple of murders, fun costumes, aesthetically striking locations, comedy, suspense—one wonders if the screenplay wasn’t shopped to Hitchcock before Donen won the gig.

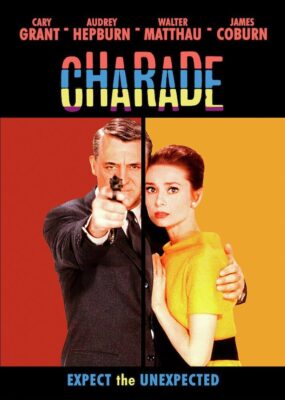

Beginning with a mysterious death, it follows the oblivious widow (Audrey Hepburn) of the deceased, who finds herself pursued across Paris by three slimy crooks (James Coburn, George Kennedy, Ned Glass) who claim her husband had stolen a small fortune from them. Who has the money? Can she trust the debonair stranger (Cary Grant) she met on vacation just before her husband’s death? Why does his story contradict the CIA official’s (Walter Matthau) information? What if she’s falling in love with him? Wait—the film opened with her discussing a divorce with her friend (Dominique Minot). Are we sure that she’s innocent? As it turns out, none of the crooks trusts the others. And when they start getting killed offscreen, beginning with Kennedy’s claw-handed brute, we start to question our assumptions about Grant’s charismatic boy scout, maybe even to stress eat some popcorn like the clueless widow.

Donen smoothly layers a variety of comedy styles—screwball antics, repeat gags, morbid humor—with a breezy movie romance and a nail-biter plot. The film opens like an Agatha Christie murder-mystery with the soon-to-be-dead man falling from a moving train in his pajamas, then cuts to its bouncy credits, then to an arm extending from the shadows while the unwitting widow enjoys a meal at a French Alps ski resort. The trigger is squeezed and… water squirts her in the face. It’s this well-considered modulation between suspense and humorous reprieve that keeps the story humming along in a playful manner.

Though it’s not quite as multidimensional as Hitchcock’s masterpieces, mostly due to a solid-for-its-genre but unremarkable screenplay (Peter Stone) that is put together with common ingredients, as well as its hesitance to explore humanity’s dark side (one area where de Palma usually comes through), it is a complete pleasure to watch as it glides through its twisty plot with an easy grace, getting incredible mileage out of Grant’s charm, his chemistry with Hepburn, Henry Mancini’s bouncy theme, and the Bond villain–esque turns from their co-stars (Dr. No had released the prior year, with From Russia with Love hitting theaters around the same time as Charade). Coming at a time when the Motion Picture Production Code was relaxing, it is a little more licentious and shocking and violent than its 1950s forebears—distasteful to many critics who caught its initial run only a couple weeks after Kennedy’s assassination placed American culture in a topsy-turvy crisis—but still fairly conventional in its morals and storytelling techniques, offering a glimmer of the joyful magic of Hollywood’s mythic golden age that was quickly vanishing from the silver screen.

The two leads find that perfect balance between fulfilling their duties as characters in a dramatic story and playing up their own screen personas. My wife and I both got a good laugh when Hepburn taps the dimple on Grant’s chin and asks him how he shaves in there, and the way that Grant smoothly shifts between aliases and laughs his way through some of the sillier jokes (e.g. wearing his clothes into the shower to carry a scene through some particularly steamy dialogue) is a testament to his ability to charm in any context. Their age gap may be problematic for some, but the script spends a few lines making light of it and the stars’ verbal sparring is so enjoyable that their passionless smooches are a nonissue.

If the film’s predilection for unsophisticated fun undermines its potential to rival films like Vertigo or Notorious, it’s as effective as Hitchcock’s entertainment-first pictures like North by Northwest and To Catch a Thief, which both incidentally star the inimitable Cary Grant.