“What’s the difference between a duck?”

The experimental work of Mike Figgis is not for the faint of heart. I remember watching Time Code in class and appreciating its central gimmick, but mostly scoffing at the result. A similarly confounding gonzo experiment, Hotel is a pretentious meta-analysis of the Dogme 95 style of filmmaking. Though the premise and initial scenes are intriguing, it proves much too sloppy, disjointed, and randomly spliced for non-ironic enjoyment. If not for the bizarrely star-studded cast—many of whom swoop in and out of a single scene in only a few minutes—I doubt anyone would willingly give this the time of day. That said, usually as you watch a film you can understand what its goal was even if it fell short of the mark; I have no idea what Figgis was trying to do with Hotel other than make a strange mess. At the very least it’s an interesting disaster.

If you have a curious bone in your body, the logline will no doubt pique your interest: a Dogme film crew shoots an adaptation of 17th century play The Duchess of Malfi while being followed by a diva documentary filmmaker and living out of a hotel where the kitchen staff feeds their guests human flesh. Kind of like a poor man’s Symbiopsychotaxiplasm with a dash of shock horror. The film shoot takes place in Venice, led by Trent Stoker (Rhys Ifans), a cocky slacker who is regularly at odds with his producer Jonathan Danderfine (David Schwimmer). Stoker appears incapable of comporting himself, let alone directing a film, referring to his artless adaptation, devoid of the poetry in the original, as a “fast food McMalfi” and describing the brutalized script as “a real tight Duchess of Malfi.” Things do not go smoothly. Cast members complain of the script alterations (Valeria Golinio takes issue with her nude scenes and lack of dialogue—“I don’t want to be upstaged by my own tits!”), one of them leaves the production for a paying gig working on a Ridley Scott film, and others are thrown off by the constraints of the Dogme style. But Stoker forges ahead with his shoot, hellbent on making something.

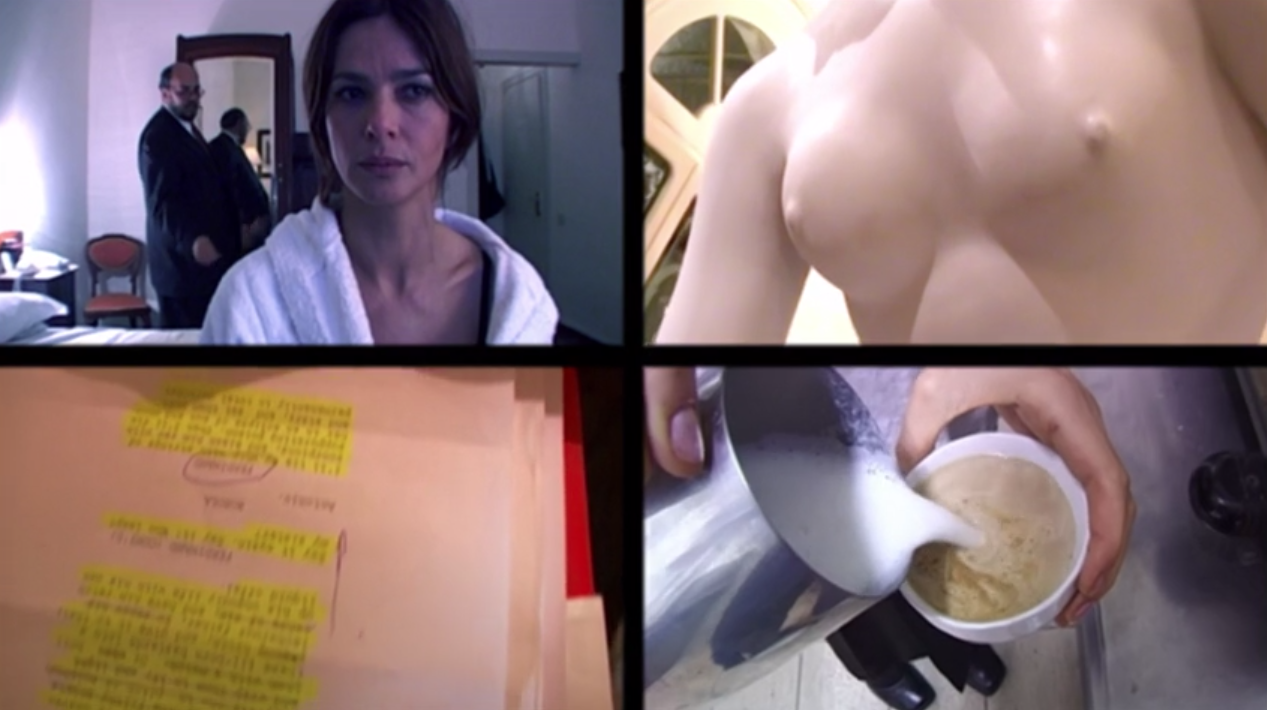

Occasional use of the simultaneous four-screen format of Time Code is mixed in as we move in and out of the fictional film and “behind-the-scenes” footage, expanding the context to include the film’s nervous financier and a hitman who plugs Stoker in the spine and leaves him in a coma. For quite a while it is assumed that the eccentric director is merely taking a contemplative rest. When they finally have him medically assessed, the doctor describes a miraculous enigma—there is no exit wound for the bullet, but the bullet is no longer in the director’s body. Once Danderfine takes over the directorial duties things become significantly less interesting.

The strangest element of Hotel is how many recognizable actors wanted to sign up for this. John Malkovich opens the film by having dinner in the catacombs below the hotel, at a table split down the middle by prison bars, separating him from his companions. His conversation is casual and odd, continually circling back to his hesitancy to eat the meat presented to him because he has high cholesterol. Burt Reynolds appears as a manager of a flamenco troupe who gives a weird almost-eulogy for the comatose Stoker. Saffron Burrows and Salma Hayek, who both participated in Time Code, return for another round of inanity. Burrows plays the Duchess of Malfi in the central production while Hayek is a primadonna documentarian stalking the film crew, interrupting their shoots, firing ditzy questions at anyone within earshot. She even asks if she can interview John Webster (directly after being informed he was a contemporary of Shakespeare). Lucy Liu appears for like two minutes and almost gets in a fist fight with Hayek. Danny Huston, Julian Sands, and Jason Isaacs all appear briefly, among others.

While I found much of Hotel baffling and inscrutable, I won’t deny that Figgis does a few things that caught my eye. Rather than shy away from the limitations of digital grain and pixelation, he embraces them by speeding up the bustle around the comatose director which blurs into a confusion of digital artifacts. To indicate the production footage, the aspect ratio changes, and other snippets are shown with a red border around the frame and/or shot in infrared to make things a little more sinister.

I just wish that some of it remained coherent beyond the momentary provocations it offers. Yes, it’s funny when a pigeon lands on an actor’s head and the director commands them to stay in character. It is weird and uncomfortable when the financier’s mistress dips her bare breasts into glasses of milk. It’s shocking when Hayek’s Charlee Boux stumbles upon dismembered limbs. I’ll refrain from saying any of the dramatics were moving because those moments exist without enough context for them to land.

Characterized by jerky handheld camera movements, rapidfire editing, improvised acting, and the ugly smear of lo-fi digital video, this meta tale of a movie production gone awry falls victim to indulgent diversions and grating aimlessness. Mike Figgis appears to be passionate about what he’s doing, so it’s unfortunate that his film amounts to little more than a pretentious exercise with a semi-famous cast posing as some highbrow arthouse effort. Without the impressive coordination evident in Time Code, the follow up from the bold experimenter just hang together.