“It ain’t a time for begging. It’s time for praying.”

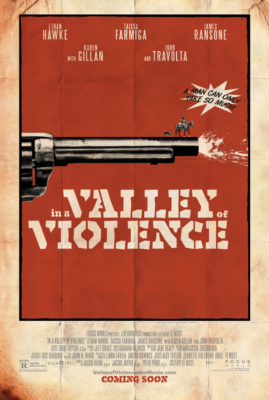

My apologies to Ti West. Picking a film to watch necessarily means not picking a bunch of other ones, and though I knew West by reputation as a solid genre filmmaker, for whatever reason I just never got around to watching one of his movies. Predominantly working in the realm of horror (The House of the Devil, The Innkeepers, The Sacrament), his In a Valley of Violence finds the director gutting the archetypes of the Western and rebuilding them with a mind toward humor, gore, and amusement.

The laconic Clint Eastwood antihero (Ethan Hawke), the pragmatic lawman (John Travolta), the loose-cannon troublemaker (James Ransone), the false priest (Burn Gorman), the forbidden love interest (Taissa Farmiga), the proper lady (Karen Gillan). The misunderstanding of the lethal drifter in the saloon, the dust-ups, the duels, the damsels. It’s all here—there’s even an update on the classic bathtub confrontation (The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, The Missouri Breaks)—much nastier than your John Wayne and Audie Murphy classics of yore, and even making Peckinpah (The Wild Bunch, Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid) look a little tamer than I’d care to admit, if not quite cohering into an totally satisfying story.

The small-scale revenge tale is kicked off in earnest when the local hooligans—led by Ransone and hiding behind badges—kill the wanderer’s dog (credited to a talented pooch named Jumpy, just in case the real-life collie ever checks to make sure I gave it proper attribution) and leave him for dead at the bottom of a ravine. He survives, of course, and then wanders back to the nearly-empty town to go on a John Wick–esque rampage, doling out death as emphatically as Oprah gives bad book recommendations. West proves right at home orchestrating grisly action in a legible manner, aided by the Morricone-inspired score from Jeff Grace.

Much of the fun comes from the script, written by West, and the actors’ enthusiastic delivery of its lines. Near the end, after buckets of blood have already been shed, with still more to come, Tommy Nohilly’s Deputy Marshal “Tubby” interrupts Travolta’s wooden-legged lawman’s frantic instructions in order to complain about his nickname. No sooner has Travolta agreed to call him Lawrence than a bullet zips through the window and claims his life. Travolta and Ransone have done outrageous characters like this before and it is their energy, combined with the desperate, childlike exuberance of Farmiga as the innkeeper, that carries the film to its ecstatic heights. Travolta is especially engaged with the material, finding hidden jokes in the lines that wouldn’t be evident on the page. But it is anchored by Hawke as the steely-eyed gunslinger—a part that feels entirely natural in the haunted first half given his past roles, but feels like a revelation when he turns menacing and ruthless in the second. At times, it does feel like the tone struggles to find a proper balance between the traumatized soldier revenge story and the Spaghetti Western pastiche, and one wishes that West had the budget to fill out his backwater town with a little more flesh and blood so the whole production didn’t feel so stagey, but one will take what one can get.

It’s not quite as brutal as S. Craig Zahler’s Bone Tomahawk, nor as wide-scoped and cynical as Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained and The Hateful Eight, nor as sophisticated as the Coen brothers’ True Grit, but it isn’t ridiculous to bring it up in conversation alongside those hyper-violent and intermittently hilarious modern Westerns that are, essentially, affectionate borderline-spoofs of the genre. I’m just happy that we get to have the conversation in an era where the non-revisionist, non-message Western has mostly gone the way of the dodo. Am I allowed to complain about people not seeing a film in theaters that I myself did not see in theaters? If so, how did this excellent film only make $61k at the box office?