“Here’s to swimmin’ with bow-legged women.”

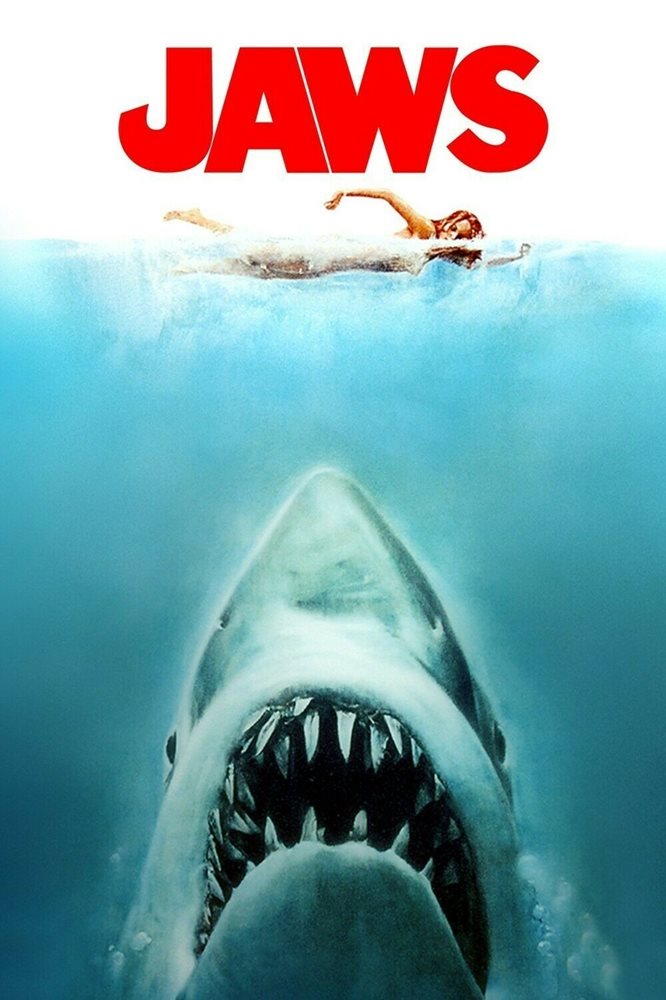

There is such a preponderance of history, nostalgia, and analysis surrounding Jaws that it’s almost miraculous that the film still matches its legendary reputation. Steven Spielberg’s breakthrough effort redefined the modern blockbuster, becoming the highest grossing film of all time and reorienting tentpole release schedules around the summer months. By whittling down the plot of Peter Benchley’s best-selling novel to its most fundamental conflict—man vs. beast—Spielberg daringly goes for the jugular in his attempt to elicit primal fear and sustains that tension throughout the entire film.

There’s more to it, of course; but audiences didn’t flock to theaters because of its depiction of masculinity in crisis, its exploration of the corruption of the powerful, or its symbolic representation of sexual predation. Jaws put butts in seats because it had an elemental cinematic magic that is a result of Spielberg’s insatiable talent and creativity forced into overdrive by a tumultuous production (and a memorable score, and great acting, and, and, and you get the point). The film gave rise to a tangled web of trends in the film industry, chief among them the new business model of throwing money at high-concept projects that cast a wide demographic net in an attempt to transcend any boundaries that would hinder their universal appeal. While this strategy has had qualitatively mixed results—and in my opinion has had a net negative effect on the film industry as a whole—Jaws remains one of its pinnacles. It’s a bona fide classic that requires very little explanation of its merits.

Aside from Spielberg’s obvious competence and stylistic flourishes (like the subtle long take during the ferry ride or the slick Vertigo-esque dolly zoom on Brody when the young boy gets attacked), one element that sets Jaws apart from other high-concept films is that the three lead characters are all well written and strongly acted. The performances by Roy Scheider as Chief Brody, Robert Shaw as shark hunter Sam Quint, and Richard Dreyfuss as oceanographer Matt Hooper feel entirely natural, as if the actors had been inhabiting their characters for years. Having only a single notable role under his belt (in George Lucas’s American Graffiti), the film launched the career of Richard Dreyfuss, leading to an Academy Award nomination for The Goodbye Girl and a starring role in Spielberg’s Jaws follow-up, Close Encounters of the Third Kind. In 1971, Scheider had major roles in Klute and The French Connection that helped solidify his status as a dependable actor, and after Jaws he took roles in Sorcerer, All That Jazz, Naked Lunch, 2010: The Year We Made Contact, and a slew of other overlooked gems. Robert Shaw, known for his roles in From Russia with Love and The Sting sadly passed away from a heart attack a few years after the release of Jaws.

But the cinematic magic that the three actors created together in Jaws came about almost by accident. In a fortuitous mishap, delays with the mechanical shark gave the team extra time to rework a script that had been rushed into production due to impending strikes.1 According to Spielberg, he took a cue from Robert Altman’s playbook and ceded some of his creative control to his cast, allowing them to develop their characters themselves. Although utilizing only three main cast members in Jaws compared to the ensembles of Altman’s films like McCabe & Mrs. Miller and Nashville, Spielberg began encouraging his actors to own their characters. Friend and comedian Carl Gottlieb had been brought on to add some humor to the otherwise dark script, and stayed on for several months. Scheider, Dreyfuss, and Shaw would go to Spielberg’s house for dinner and improvise scenes with Gottlieb, who would polish them up the night before shooting. These sessions are why the film’s final third—when they face off with the shark—is so tightly performed and features unmatched camaraderie amongst the men. The chemistry is outstanding, and this disparate trio who had only just met become believable brothers in arms. Gottlieb, who plays the newspaper editor in the film, also penned the behind-the-scenes book The Jaws Log, which chronicles the tumultuous production.

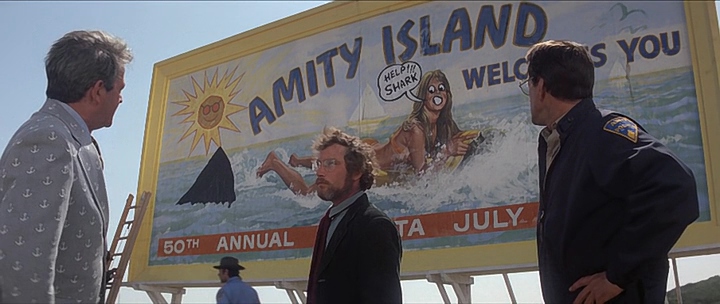

The story is very streamlined and is much less complex than the novel from Benchley (who co-wrote the screenplay), cutting out nearly every subplot and minimizing the family drama; though what family drama is left over covers a lot of emotional ground in a short amount of screen time. After the memorable opening sequence that introduces us to the threatening man-eater, Chief Brody must battle with the Amity Island’s mayor (Murray Hamilton) to keep the people safe while allowing the town to prosper from the influx of visitors on the 4th of July. At a town hall meeting, rugged seaman Quint offers to hunt down the killer shark for $10,000. Before taking him up on his offer, the town brings in shark specialist Matt Hooper to analyze the situation. The narrative moves at a quick pace. Wild go-getters flock to the area when a reward is offered for the shark; a false victory is attained when a smaller shark is hauled in; a few close calls raise the pulse without giving us a clear glimpse of the threat; and we soon find ourselves with Brody, Quint, and Hooper aboard the Orca.

As I have said, what elevates Jaws is this latter portion of the film, where the three men hunt for the shark. In lesser hands, this could have been a thrilling yet forgettable ending. But in the capable hands of Spielberg and company, we are treated to masterful buildup and climax. Two things in particular stand out to me whenever I revisit the final third ofJaws. The first is how lighthearted they were able to make the scenes without ever giving up an inch of dramatic tension. Hooper’s general goofiness—making faces at Quint behind his back, bursting out in song when he gets drunk, throwing his leg up on the table to show off his scar—allows the talkative yet emotionally impenetrable Quint to open up a little, resulting in one of the movie’s best scenes. Although it remains a bit of a mystery who is primarily responsible for penning it, Robert Shaw delivers a chilling monologue about his survival of the sinking of the USS Indianapolis. The Navy submarine had delivered parts of the Little Boy atomic bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima before being torpedoed and its crew stranded for days in shark-infested waters. The scene is absolutely masterful in its execution and placement within the film; the monologue is delivered perfectly by Shaw and in my opinion it is more harrowing than any of the scenes featuring the shark.

While Spielberg would go on to create a number of personal films like E.T. (1982) and Schindler’s List (1993), he joined the production of Jaws as a hired gun, beginning work on the film before his debut studio feature The Sugarland Express was even in theaters.2 I feel it is pertinent to note that fact because over the years a number of abstract analyses have been imaginatively read into the film, i.e. it’s a retelling of the Watergate scandal; it’s about masculinity in crisis; the shark represents a serial killer or a sexual predator, etc. The latter may hold some weight, as the audience is presented with shots that represent the shark’s point of view. Sneaking around beneath the surface, the camera gazes upon the bare legs of swimmers treading water before going in for a kill. The “monster POV” technique is primarily utilized in horror, in films like Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom (1960) and John Carpenter’s Halloween. Popular film analysis would suggest that using such a POV is meant to force the viewer to identify with the killer, but I would argue (in the case of Jaws) that its use simply heightens the tension that the viewer feels because crucial details of the scene are kept from them (namely, the physical description of the monster). In Halloween, it makes you feel uncomfortable to see “yourself” stabbing someone, but that doesn’t work here because you don’t feel like a shark. To put it simply, Spielberg just wanted to make a good movie; he wasn’t overly concerned with social commentary or subtext.

The film itself is undeniably one of the classics of its era and it holds up very well nearly half a century later. If I have an axe to grind it is with the film’s legacy. I don’t begrudge the ripoffs3—some of them, like Piranha (1978), are actually pretty good—but the use of its marketing and storytelling methods as templates. Many “firsts” occurred with Jaws. It was the first film to extensively utilize trailers on network television. Along with The Godfather (1972), it helped usher in the era of nationwide releases (films used to open in a single theater and slowly spread across the country). The film also became the first summer blockbuster; in prior decades, air conditioning had not been commonplace, and summers had typically been slow months for theaters. Several other films had seen summer releases in the years leading up to Jaws—Bonnie and Clyde (1967), Easy Rider (1969), American Graffiti (1973)—that indicated the opportunity was there, but Jaws was the first to really capitalize on it. The combination of all of these things led studios to focus their efforts (and their money) on “high-concept” films,4 which quickly led to the demise of the fondly remembered New Hollywood era, when large studios threw money at auteurs and gave them creative control over their passion projects.5

Many classic films require the viewer to do some background research in order to fully appreciate them. Sometimes you need to understand what novel trick the film pulled off that was new at the time—cinematographically, narratively, what have you. Sometimes you need to understand the cultural context in order to understand its impact. New Hollywood in general, and Jaws in particular, need no such qualification. Forget all of the analysis; it’s simply great cinema.

1. The calamitous production doesn’t quite rival the likes of Apocalypse Now (1979) or Heaven’s Gate (1980), but it wrapped way over budget and behind schedule owing to Spielberg’s inexperience and hubris (he was adamant they shoot at sea instead of in a tank) and a faulty animatronic shark. The production was so disastrous that Spielberg thought he may never again find work in Hollywood. (As evidenced by the film’s incredible success and a Spielberg’s heralded career, his fear did not come to pass.)

2. Spielberg had also directed cult classic made-for-TV movie Duel in 1971.

3. Alien (1979) was marketed as “Jaws in Space,” while a smattering of other “creature features” were pumped out throughout the 1970s and 80s, including Grizzly (1976), Claws (1977), Tentacles (1977), Orca (1977), Alligator (1980), The Edge (1997), and Deep Blue Sea (1999). Even recent films like Sharknado (2013) and The Shallows (2016) would likely not exist without Jaws; and the Discovery Channel’s popular “Shark Week” programming owes its popularity to Spielberg’s film as well.

4. High-concept sounds like it should mean “smart” or “complex,” but what it actually means is that the film can easily pitched and marketed, e.g. “An aquaphobic police chief hunts a gigantic, man-eating shark in order to protect the citizens of his town.”

5. Undeniably though, Jaws and Star Wars (1977)—the two biggest culprits in the demise of New Hollywood—also belong to New Hollywood.

Sources:

“Jaws—The Monster That Ate Hollywood”. PBS. 2001.

Biskind, Peter. “Easy Riders, Raging Bulls”. Simon & Schuster. 1998.

Hays, Matthew. “A Space Odyssey”. Montreal Mirror. 5 June 2011. (Archived).