“Blues help you get out of bed in the morning. You get up knowing you ain’t alone.”

In the middle of Bob Dylan’s song “Tombstone Blues”, which I’ve listened to approximately half a million times, there is a stanza that goes: “Where Ma Rainey and Beethoven once unwrapped their bedroll/Tuba players now rehearse around the flagpole/And the National Bank at a profit sells road maps for the soul/To the old folks home and the college.” This was at a point in Dylan’s career where he was writing in a stream of consciousness mode which resulted in some memorable but impenetrable lyrics. Also mentioned in the song are Galileo, John the Baptist, Jack the Ripper, Paul Revere, and Cecil B. Demille. I still don’t really know what it all means, and kind of doubt Bob Dylan ever did. I actually didn’t realize that Ma Rainey was more than an offhand Dylan lyric until I discovered Blind Willie Johnson and went on to have my mind blown by gradually listening through the history of blues music. Although the surviving recordings of the “Mother of the Blues” are unfortunately of very low quality, there’s a reason she earned the moniker. She was one of the first to put her songs to wax in the 1920s, and wrote many of them herself.1

Ma Rainey died when my great-grandfather was a teenager; her musical contemporaries were names like Bessie Smith, Charley Patton, Leadbelly, and Robert Johnson. Unless you’re legitimately into blues music, certain strains of classic rock that were heavily influenced by the genre (the Rolling Stones particularly “borrowed” quite a bit), or the history of recorded music, those names might not mean anything to you. Perhaps these artists had more of a cultural presence in 1982 when August Wilson’s play was first performed, but I doubt it. Four decades later, as the play has been turned into a film, I have two friends that listen to blues music and I would guess one of them has heard of Ma Rainey outside of the Dylan song, but that neither of them have listened to her.

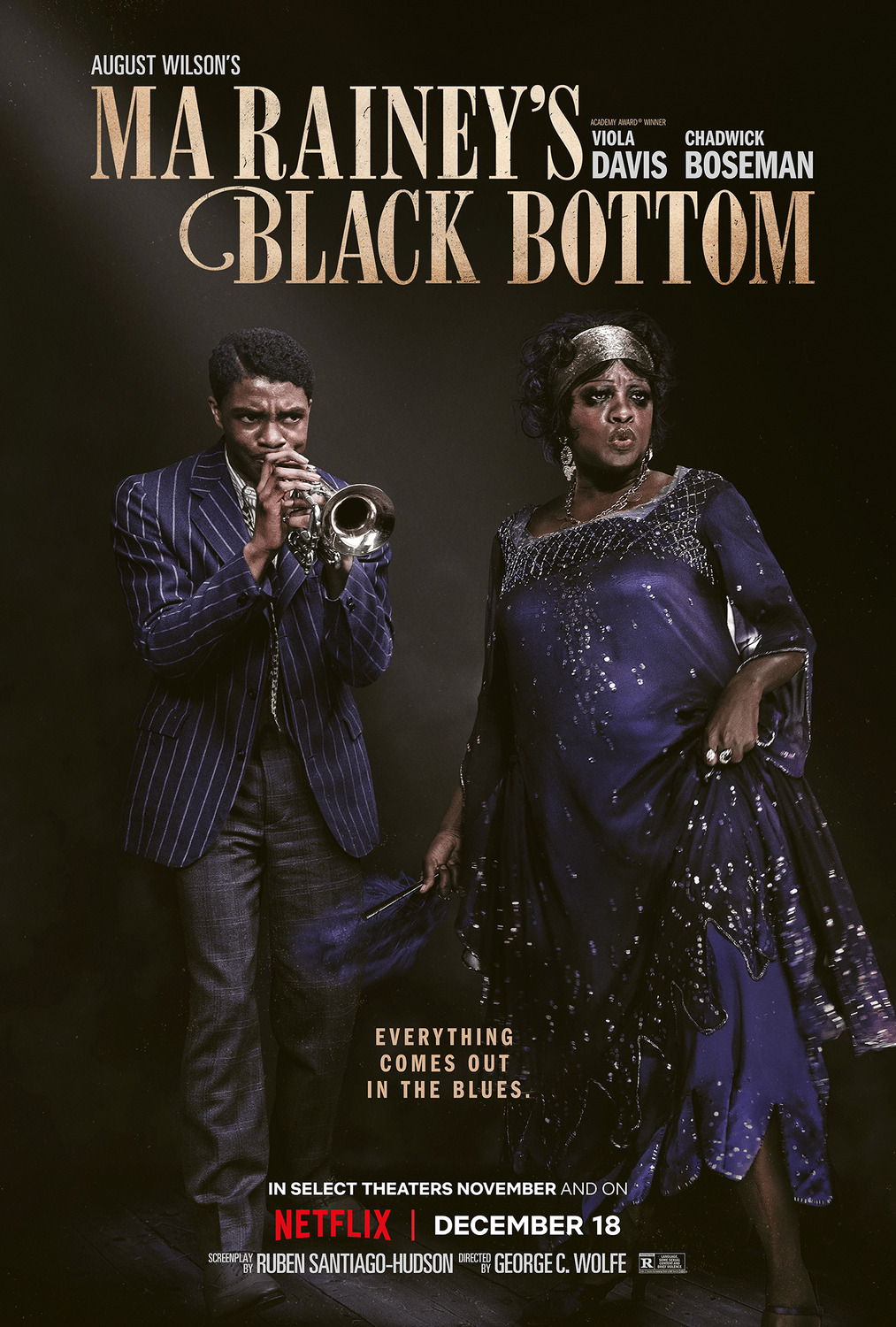

Considering the source material, which limits the locational scope of the narrative mostly to the bowels of a recording studio, the success or failure of Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom hinges entirely on its performances. And it succeeds largely because of two of them in particular. Viola Davis puts in a startling turn as the titular Ma Rainey, bringing the rambunctious singer to life. Her performance is committed—she’s heavier than her usual roles call for, and spends the duration covered in greasepaint and with silver caps on her teeth. Similarly committed is the late Chadwick Boseman, performing in his final acting role as Levee Green, a cornet player in Ma’s band with all sorts of pent up emotion that comes boiling to the surface during the course of a recording session. Thankfully, the play, and hence the film, is not a rote biopic, but a fiery tale that mixes fact and fiction while remaining true to the iconic figure that it’s based upon. It highlights the historical struggles of black Americans, but also displays a unique culture, rich in art and style, that the racketeer could mimic but not replicate. This modest little chamber drama, directed by playwright and director George C. Wolfe, has the tough task of celebrating the legacies of three key figures—Rainey, Wilson, and Boseman. It largely succeeds on account of Ma Rainey and Chadwick Boseman, but leaves too much of the nuance of Wilson’s work on the cutting room floor.

The most noticeable deviations from Wilson’s play are a suitable intro scene and an agenda-laden coda. The intro is meant to subvert expectations, showing two young black men running through a field at night only to arrive at a tent concert where Ma Rainey performs ‘Deep Moaning Blues’. It’s a solid introduction to the enigmatic character and a very good musical performance in its own right.2 The other departure from Wilson’s play is the ending, which re-emphasizes a point heavily implied by the preceding scenes, and I found it unnecessary. Black Bottom was the second cinematic adapation of Wilson’s “Pittsburgh Cycle”—a ten-play chronicle of the African-American experience in the 20th century—and the only one to take place outside of Pittsburgh’s Hill District—his hometown. Denzel Washington’s Fences was the first to be adapted, while the other eight are reportedly in the works.

The film adequately captures Rainey’s larger than life persona and her obstinate demeanor. Viola Davis plays her with an appropriate disregard for authority, intent on getting her own way or walking out of the session. There’s very little compromise in Ma which leads to some fun exchanges. Her interactions with her manager (Jeremy Shamos) are particularly delightful. The singer’s bisexuality3 is only touched upon; it’s used to spark some drama rather than being forced upon the viewer as a standalone statement. (Those with moral hang-ups about such things should find themselves more upset by a salacious scene involving Levee, Ma’s promiscuous young girlfriend Dussie Mae (Taylour Paige), and a locked door.) While I really enjoy Davis’s contribution to the film, I felt that Rainey’s no-nonsense attitude was too often relied upon for comedic effect. By the end of the film, she seemed partially reduced to caricature, which I don’t think was the intention. But it’s a really solid performance.

Chadwick Boseman plays the ambitious and charismatic young Levee with fire in his belly, crafty with his words, talking a mile a minute. It’s possible that Mr. Boseman knew that Black Bottom would be his swan song. It’s also not outside the realm of plausibility to believe he accepted the role because of its poignant moments in which Levee’s emotions spill out in spittle-filled tirades. There are two scenes in particular, in which Boseman is tasked with delivering tearful monologues, that gives the film its heart. The speeches are saturated with ideas of death and God and justice, and, wrapped up as they are with Boseman’s own death prior to the film’s release, they are incredibly moving.

That’s not to take anything away from the role players either. Ma’s backing band, consisting of Cutler (Colman Domingo), Toledo (Glynn Turman), and Slow Drag (Michael Potts), are all portrayed by consummate professionals. Their lines are less consequential than those of Levee, but the banter reveals a deep commitment to the musical craft—a simple joy in the creation of sound that is only made possible by years of discipline. They’ll play for money, sure, but it’s a privilege to make a living doing what they love. They’re humble and content, which clashes mightily with the dollar signs Levee sees on his musical horizons. Levee even butts heads with Ma, who wants to play her old school blues the way she knows how, not in some newfangled style that Levee wants to pioneer. The contrast between Ma and Levee is really striking—she will talk roughly and bully people around but is completely willing to leave money on the table and walk away; he speaks with a silver tongue but has excessive emotional investment in his own success and believes he deserves it because of his past suffering. It’s this disagreeable cocksureness that ultimately leads to his downfall.

In the film’s final moments, Levee asks the studio owner, Mr. Sturdyvant (Jonny Coyne), about the songs that he has written and hopes to record with his own band. Unruffled, Sturdyvant tells him that he has looked at the sheet music but that they’re just not what he’s looking for. Levee pleads his case, but the best Sturdyvant can do is give him $5/apiece for his troubles. In the second major deviation from Wilson’s work, the film actualizes what is implied by Sturdyvant’s offer, concluding with an all-white band dispassionately playing through Levee’s composition. I thought the implication was sufficient, but for less attuned viewers, the stark reality of exploitation might only become real to them by seeing it in such stark relief.

Outside of a single trick where still photographs are brought to life, the fact that Black Bottom is a play is a little bit too evident. That does not detract from its power, but it certainly doesn’t help in justifying its existence as a film. Another minor complaint is that screenwriter Ruben Santiago-Hudson’s changes were too deliberately made to modernize the struggles the characters faced. They are not overbearing but they do streamline things, erasing or marginalizing the notions of artistic struggle, camaraderie, spirituality, and achievement that are more fleshed out in Wilson’s play (which runs much longer than the film). Also minimized, perhaps intentionally, is any discussion of religion outside of Levee’s diatribe against “Cutler’s God.” This means that Boseman’s centerpiece monologue—which is very good and will live on as one of his finest moments—seems to take aim at a shallow modern understanding of God rather than the more robust spirituality of the era. It’s obviously the filmmaking team’s prerogative to lean toward didacticism, but I would have preferred a little bit less grandstanding and a little more blues.

Complaints aside, it’s still a very good film, mostly because of Wilson’s solid writing—much of which survives untouched—and the performances from Davis and Boseman. I could have done with additional recreations of Ma’s songs, but beggars can’t be choosers, and it’s not like movies about the 1920s blues scene come along very often.

1. Of course, the story behind the low quality of Rainey’s music is more complicated than just the fact that they were early. They also suffered because her label was a subsidiary of a furniture company who scrapped all the originals when they went out of business during the Great Depression.

2. Ma’s vocals were handled by Maxayn Lewis, a prolific backing vocalist who has made records with many classic rock greats.

3. Ma Rainey was married to Will “Pa” Rainey when she was a teenager, but he died when she was in her early 30s. Then, as the story goes, she developed a taste for women. Or, at least, was less shy about her taste for women. This occasionally came through in songs lyrics, the most famous example being ‘Prove It On Me’. Some other stories exist, floating around the margins, regarding all-female orgies, etc. Some even say that Bessie Smith, whom Ma mentored, was a romantic partner.