“It rubs the lotion on its skin or else it gets the hose again.”

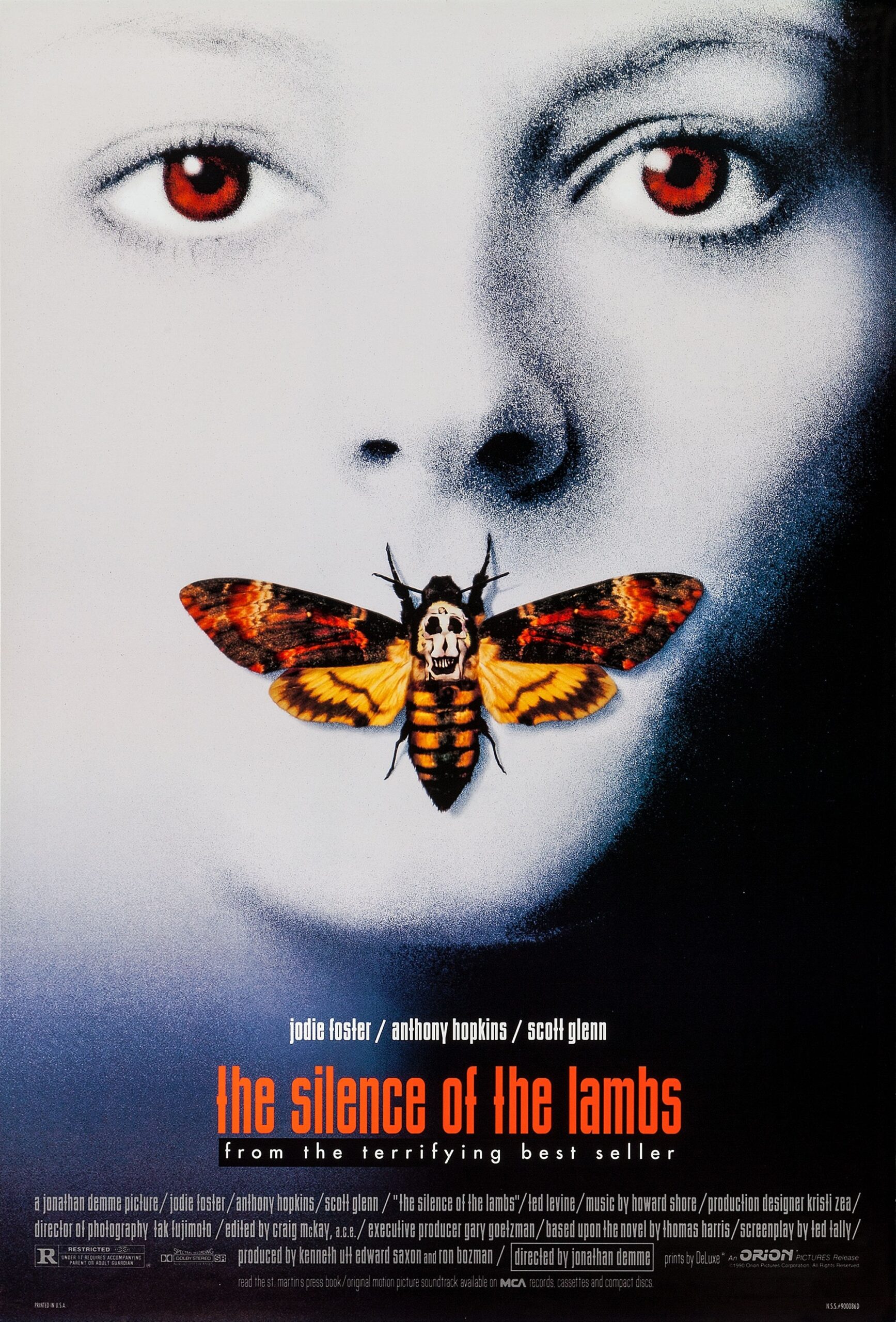

A sociological analysis of Jonathan Demme’s unimpeachable serial killer classic The Silence of the Lambs would necessarily have to contend with audience sympathy for Hannibal Lecter (Anthony Hopkins), the brilliantly perceptive psychiatrist held in a maximum security facility for killing and eating his patients. He’s a fiend, no question about it, but contrasted with the grimy, perverse transvestite Buffalo Bill (Ted Levine) whose pathology drives him to diligently knit a garment out of human skin flayed from victims lured and held captive in his basement lair, whom Lecter is tasked with psychologically profiling in a deal brokered by vulnerable FBI student Clarice Starling (Jodie Foster), the mild-mannered cannibal becomes, in the words of Jonathan Rosenbaum, “saint, guru, seer, and soothsayer rolled into one.”

Ew, wait, really? You bet. As he divvies out his insights, a quid pro quo arrangement sees the green interlocutor sharing childhood traumas with him, leading her and the audience to view this probing monster of a man as an unfathomably wise father figure, even though her own resolute supervisor (Scott Glenn) takes pains to respectfully fulfill that role. Rosenbaum’s additional (correct) point is that, though the film has a literary gloss to it thanks to author Thomas Harris’s journalism background, it exploits any psychological or symbolic perspicacity conjured by Lecter and Agent Starling’s counseling sessions in order to generate lurid thrills. Demme is after all a disciple of the great Roger Corman (who gave Demme his start on the exploitation film Caged Heat and makes a cameo in The Silence of the Lambs as the director of the FBI).

And so I hate to sound this pretentious but what happens is that a gross story that would be dismissed out of hand if it were presented without the majesty and panache brought to bear by Demme and his team (screenwriter Ted Tally, cinematographer Tak Fujimoto, editor Craig McKay, composer Howard Shore, production designer Kristi Zea, many others) becomes a media object that many view as a sophisticated artwork of great emotional and psychological depth. Maybe even moral fortitude. I mean, Lecter references Marcus Aurelius, for Pete’s sake! He draws pictures of Clarice and tells her that the world is a more interesting place with her in it! The film was only the third ever and still the most recent to win the five major Academy Awards, surely it deserves to be taken utterly seriously.1

Unless we want to reverse dolly zoom all the way out to consider the role of art in the moral formation of the general culture (which is a fine argument to have and one that Rosenbaum hints at), I would argue that we should simply chalk this phenomenon up to undiscerning audiences who’ve consistently misunderstood and mistakenly elevated certain films/books/music just because those particular things are exciting and made with superb craftsmanship. It should be obvious that just because The Rolling Stones’ ‘Brown Sugar’ makes you want to shake your hips, it doesn’t condone slavery or rape, right? This is exactly how we should view The Silence of the Lambs. It’s thrilling, a little sinister, made with extreme professionalism, ingenuity, and thoughtful restraint in the presentation of its darker elements, but ultimately this is an ultra-slick slasher film. That it is viewed as the cinematic equivalent of, I don’t know, Blood Meridian, is no fault of the film itself.

Anyway, where am I even going with this? I think, what I really want to say is that if we remove The Silence of the Lambs from the company of the arthouse films and renowned, rousing blockbusters among whose company it usually finds itself, and instead set it amongst the deep pool of slashers, psychological thrillers, exploitation films, and police procedurals that precede and succeed it, it’s more or less a unanimous best-in-class. Its story is titillating, its characterizations (on the page and on the screen) are rich but appropriately bounded and campy where appropriate, its “direct address” dialogues are gripping, it intuitively and elastically plays with time, it lets its role players shine in the interstitial moments.

It is the perfect mature blockbuster, and I’ve seen it and been thrilled by it probably ten or twelve times, but I’ve never left a viewing with the impression that the film has a deep message, or an enduring mystery, or any philosophy worth pondering. I guess you can get some mileage out of the idea that Starling is a young woman hunting a man who kills women, who in fact wants to be a woman, while acting performatively to survive in this man’s world and being treated pretty terribly by most of the men she encounters—except, of course, for Lecter, who treats her as an intelligent individual with valid thoughts and feelings just as she treats him as something other than a sideshow freak. Lecter has been compared to Frankenstein’s monster, Nosferatu, King Kong: the misunderstood monsters who act only according to their nature. In Life Itself, Roger Ebert even refers to Hannibal Lecter as a Good Person; an admission that says more about Ebert’s worldview than anything else. My preferred interpretation of Lecter is laid out well by Steven D. Greydanus, and can be summarized by saying we just don’t expect embodiments of pure evil to be cultured and sophisticated. We don’t envision serial killers who listen to classical music, sketch “the Duomo seen from the Belvedere” from memory, and know which wine pairs with liver and fava beans. Anyway, that’s all there if you need it. But all of that stuff is carried by Foster’s nuanced performance, as well as Hopkins’ extravagant one, and smartly integrated by Demme’s sophisticated direction so that—well, so that it can be exploited for exquisitely trashy thrills.

I could probably storyboard this film from memory, but my lasting impression is not based on its subject matter or even its (precise but implausible) narrative but on its craft: the giallo lighting of the underground prison; Lecter’s intro; the cut that takes us from Starling’s sparring session to a car chase… that is a different squad’s training exercise; the slick two-second shot that breaks up a car ride to indicate an overnight drive; the use of the totally unknown song ‘Goodbye Horses’ during Buffalo Bill’s striptease to remind us we are watching a Demme film; the way on the umpteenth rewatch some of the line deliveries that were initially distressing or suspenseful take on comedic undertones (“I, myself, cannot.” “Are you up there, you little shit?”); Bill’s “moth pose” vs. the grotesque spread-eagle arrangement of the gored officer’s gut-spilled corpse after Lecter’s escape; the show-stopper cross-cut when we finally come face-to-face with the villain; the green monochrome night vision scene. In fact, I considered skipping a review of the film altogether and simply making a list of things I like about it in the mold of Alex Withrow’s “X Things I Love About Y” blog posts.

All that to say, skip the sociological analysis. Demme’s best films are always multilayered with rich characters, outsider charm, and high-caliber craftsmanship. But they’re hardly deep in the sense that they should be looked at for moral, philosophical, intellectual, or emotional formation. The Silence of the Lambs is no different, but it also has more tension and brisker pacing than anything else the man ever made.2

1. Interestingly, the two other films to sweep those awards provide a nice contrast. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, about the maltreatment of patients at an insane asylum, is taken quite seriously for its depiction of mental health issues and abuses of power. It Happened One Night, on the other hand, is easy to categorize and enjoy as a high-caliber comedy.

2. Some of Demme’s fans considered The Silence of the Lambs to be a sellout, an accusation which is not without some truth to it. However, as a big proponent of Demme’s ‘80s films (Stop Making Sense, Something Wild, Married to the Mob), I find enough carryover of his idiosyncratic humanism to enjoy it as both a Demme film and a sublime thriller. In addition to selecting obscure music that perfectly meets the needs of his scene, Demme also provides a bunch of small, memorable roles for characters actors (Anthony Heald, Brooke Smith, Danny Darst, Tracy Walter, Chris Isaak, Charles Napier, Frankie Faison, Dan Butler, Paul Lazar, Leib Lensky), and uses light social commentary (Starling as the young, inexperienced, female agent in a violent man’s world; Buffalo Bill as the marginalized freak) and extreme close-ups to heighten emotions. And though I spent a good number of words suggesting the film isn’t trying to “say anything” about serial killers in general, that doesn’t mean the layered characterizations of Lecter, Starling, Buffalo Bill, and even Catherine Martin (Smith) aren’t among its chief assets.