“If you never make a choice, anything is possible.”

Jaco Van Dormael bites off more than he can chew with Mr. Nobody, but to be honest, it’s more than pretty much any director could conceptually handle. He takes on Big Ideas—the butterfly effect, string theory, immortality, future dystopia, the unquantifiable nature of time, the loss of memory as we age, chaos theory, clairvoyance, space travel, time travel, the spirit prior to birth, the understanding of self in childhood, marriage, divorce, death, love, childhood trauma. He throws them all into a mixing bowl and tries to massage the resulting concoction into an existential sci-fi romance. The breadth of his ambition is undeniable, and he proves capable of conjuring evocative, quasi-mystical moments seemingly at a whim. But as stirring and forceful as Mr. Nobody may seem at times, its puzzling blend of alternate realities, failed romances, and a wickedly dystopian future never quite amounts to what one would hope for a project presented with such self-assurance. The primary failure here isn’t that the film doesn’t add up logically—plenty of good films don’t—but that it strings you along, anticipating a unifying climax that never comes. And the journey doesn’t quite feel worth it for its own sake alone.

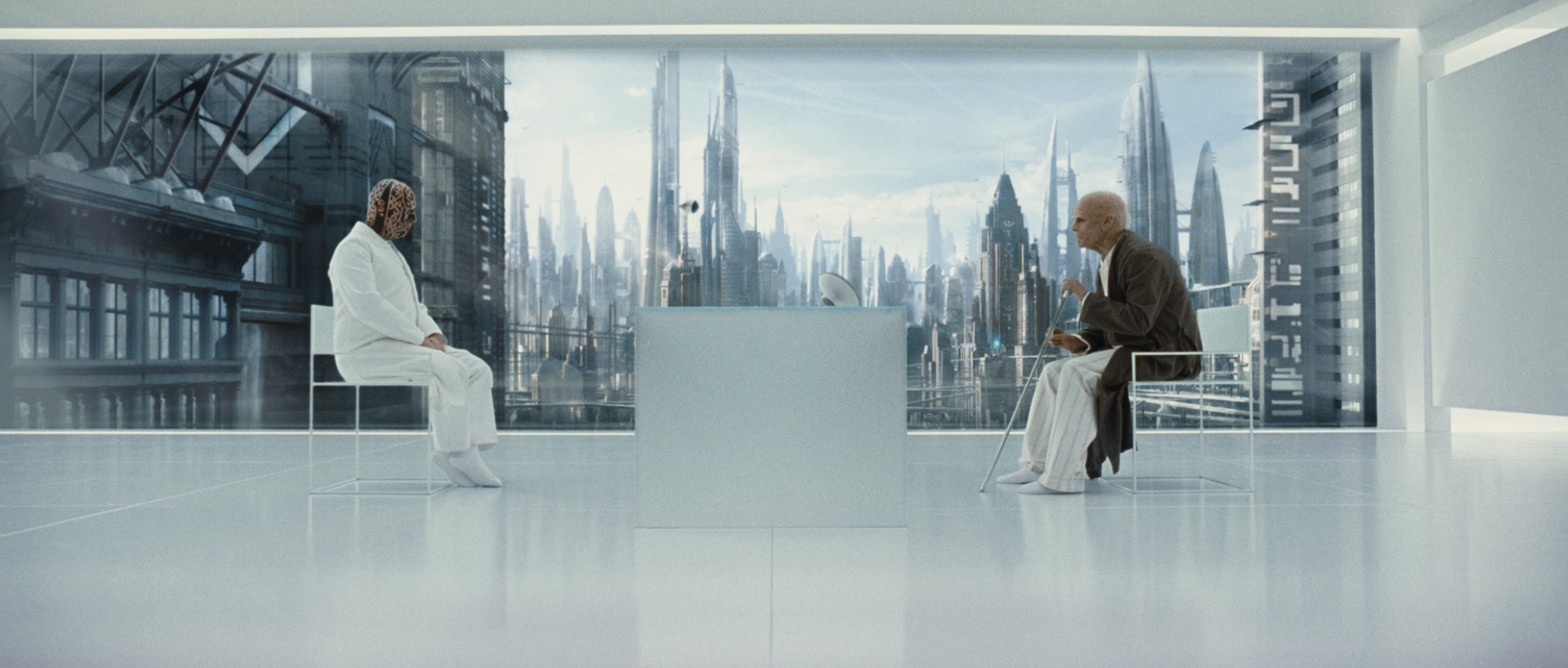

The main conceit here is that our protagonist, Nemo Nobody (Jared Leto), is unmoored in time and space. He can see the future—all possible futures, in fact—and when a young journalist breaks into Nemo’s hospital room to interview the 118-year old, he croaks out a scattered recounting of his life that is littered with contradictions, indicating that he may have lived these alternate realities. But which one is true? It’s 2092, and Nemo is the last mortal man on earth, everyone else having achieved quasi-immortality through a novel medical treatment. His story and his impending death are of popular interest, and he’s hypnotized by a doctor with face tattoos (Allan Corduner) who attempts to extract his earliest memories. After a brief sojourn through early childhood, his retelling begins rapidly jumping between four eras—age nine, around the time his parents divorced; age fifteen, when he falls in love for the first time; age thirty-four, when he’s settled into adulthood; and back to the “present,” where he’s nearing death at the ripe old age of 118.

Perhaps the most imaginative scene in the film is Nemo’s memory prior to birth. In his mind’s hypnotized eye, a unicorn begins prancing across a hazy, white, featureless plain while dozens of diapered children mill about. Hans Zimmer’s exquisite “God Yu Tekkem Laef Blong Mi”—which sounds like a chorus of celestial chipmunks (also used to great effect in The Thin Red Line)—plays while the Angels of Oblivion come and select the souls that will become human. Nemo explains that prior to their selection, each of them is omniscient. It’s only when they’re selected that their future memories are erased. But the Angels mistakenly choose him without erasing his memory, and so throughout his life he is struck by paralyzing visions of all of his possible futures.

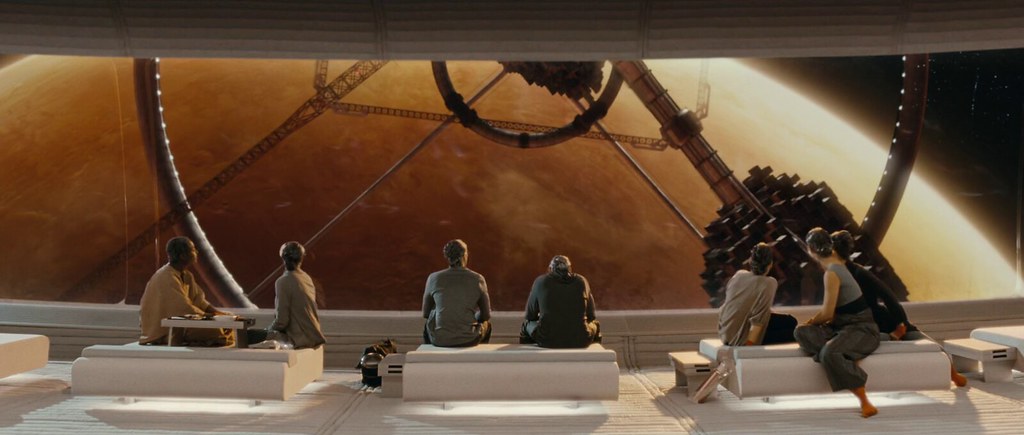

We move through Nemo’s childhood in the first person, as the inquisitive boy struggles to grasp concepts that have become background noise for adults: I can see mommy and daddy, but not myself. Since I can’t see myself, maybe I’m not real. Why am I me? Why, once the smoke comes out of the cigar, can’t it go back in? Adult Nemo, who in one possible future is a popular science guru à la Bill Nye, is featured in television lectures where he speaks about string theory, spatial and temporal dimensions, and entropy. In some of these lectures, he has burn scars on his face because in some of his possible pasts/futures he and his wife Elise (Sarah Polley) are caught in the blast when a tanker truck explodes. Sometimes she dies in the accident, but in other timelines, she suffers from depression and personality disorder once they have kids. In one of the futures where she dies, Nemo travels to Mars on a futuristic spacecraft to fulfill a promise to spread her ashes on its surface. On the ship to Mars, he meets Anna (Diane Kruger). In a different potential reality, his divorced mother begins seeing another man and young Nemo (Toby Regbo) falls in love with teenage Anna (Juno Temple), creating a stepkids-in-love scenario that leads to an existential crisis when their parents stop seeing each other and Anna moves across the country with her father. Later, they meet in a crowded train station and either rekindle their teen romance or don’t.

In still another timeline, a young Elise (Clare Stone) rejects Nemo. Using his clairvoyant abilities, he decides to never leave anything to chance ever again. He chooses to marry Jeanne (Audrey Giacomini) simply because she is willing to dance with him. He uses his foreknowledge to ensure that they have a perfect life—big house, swimming pool, two kids, the finest clothes. But once they reach this ideal scenario, Nemo finds himself disassociated from his “perfect life,” bored, and frequently becoming lost in his thoughts of his other lives that left some things to chance. And he clearly does not love his wife, who realizes that he’s never “there.” In the Jeanne storyline, Nemo becomes so disillusioned that he begins making every decision by coin toss, eventually leading to his death at the hands of a gangster’s handgun—one of dozens of potential endings for Nemo.

Many of these fractured scenarios pass with an air of believability, as melodramatic as they may seem. But then, interspersed between these are scenes that call to mind the brain ticklers of Charlie Kaufman or The Truman Show, where the protagonist begins to suspect that something is fundamentally off with his conception of reality. Helicopters transporting “blocks” of water and dropping them into place in the ocean like Legos; a giant foot descending from the sky and crushing a building; cities disintegrating; construction workers rolling up a section of asphalt like a carpet; everyone suddenly clothed in argyle. These jarring transitions, sometimes linked by visual motifs, are all very skillful, often transitioning on shocking images into the ironic use of songs like ‘Mister Sandman’ and Buddy Holly’s ‘Everyday’. Taking all of this in, one gets the impression that Van Dormael is maybe just showing off rather than vying for any specific point or even aiming toward a conclusion—logical, thematic, or otherwise. That in the writing of his complex narrative he became too intoxicated with his own creation.

The question of which of Nemo’s tragic lives is the real one doesn’t really have an answer, nor does it need one. Eventually, the adult Nemo meets the old man Nemo on a television screen and is told that neither of them are real, that they both exist in the clairvoyant imagination of a nine year old boy who can see all possible futures but cannot decide which parent he should choose when they part ways. As the old man Nemo tells the reporter in his hospital room, he’s stuck in a situation that chess players call a zugzwang, where the best move is not to move. But time moves, so what can you do? Not choosing is a choice. It ends with the universe reaching its max expansion, then beginning to contract as time begins moving backwards.

Mr. Nobody is engrossing, stylish, and existentially challenging. At its best, it is reminiscent of reality-jumping films like The Fountain or Cloud Atlas. But in expanding his scope to encompass so many different ideas, themes, and motifs, Van Dormael finds himself overwhelmed, unable to successfully corral his tangents into a sufficiently coherent work. The portions where Nemo lectures into to the camera are the filmmakers’s platform to preach directly to the audience. He uses these scenes to discuss the nature of the universe and to reassure the viewer that the scientific theories that underpin his fractured narrative are legit. Regardless of their correctness, none of them are worthy of the mystical reverence that Mr. Nobody is trying to stir up in the audience. At one point old man Nemo explains that he lost Anna because an unemployed Brazilian hardboiled an egg. Okay, that’s the butterfly effect, now what?

Van Dormael stated that he wrote the screenplay because he wanted to cinematically convey the existential dread that he feels when facing “the abyss that is the infinity of possibilities.” I think he captures that adequately, but comes to a faulty conclusion. As ancient Nemo finishes his interview, he tells the confused reporter, “Every path is the right path. Everything could have been anything else and it would have just as much meaning.” This is a terrible outlook on life. E.g. if he had murdered his children or divorced his manic wife, would those actions have just as much meaning? And if so, then maybe we shouldn’t be elevating “meaning” as the highest good?

I obviously have my frustrations with Mr. Nobody, but there’s so many things that I thought were brilliant that I’m on the fence about whether or not I love it. For most films, even if everything goes perfectly, from script to production to editing, they max out at various levels of merely good. Mr. Nobody aimed for the stars. If Van Dormael would have matched his potential here this could have been an existential cinema classic. Maybe it still is. It’s at least very good as an exploration of the potential directions life can take and the outcomes we unknowingly preclude by making everyday decisions. I am a fan of the madcap fractured presentation of the narrative, the inclusion of fictional elements like the Mars trip, the surreal imagery, and the rampant ambiguity. While Van Dormael’s philosophical viewpoints definitely don’t jibe with my own and he forces his drama a little bit, his visionary ability to evoke wistfulness across a vast, far-reaching story is superb. My hang ups with the conclusion aside, Mr. Nobody is a whimsical sci-fi brain teasers that will really make you think, and I’m always up for another one of those.