“We may not enjoy living together, but dying together isn’t going to solve anything.”

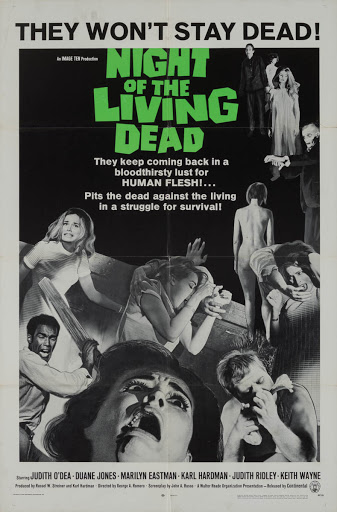

From the dawn of cinema through most of the 1960s, horror movies were entirely different than they are today. In the mid-twentieth century, Universal Studios had a run with famous monster films (Dracula, Frankenstein) and German expressionist directors had success with films like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and Nosferatu. In the ‘50s, during the atomic age, many horror films featured mutated beasts and other oddities evolved as a result of nuclear radiation. But when the Hays Code was abandoned, filmmakers were quick to move from rubber costumes and fancy make-up to more visceral fare with the intention of really giving moviegoers a shock. Writer-director-cinematographer-editor George A. Romero was one of the first to produce a truly terrifying horror film, independently releasing the ghastly Night of the Living Dead on unsuspecting teenagers before a rating could be attached to it under the new system (which meant kids could buy tickets). Drawing heavily on Richard Matheson’s crucial 1954 novel I Am Legend, Romero’s film is startling and immediate, horrific and unconventional, unlike anything audiences had seen before. It’s a resounding success as a film, a singular historical artifact, and a great inspiration for aspiring artists who feel a strong urge to simply get out there and make something.

There had been minor breakthroughs in the direction of terror, body horror and bloodshed; Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho is an obvious precursor, and two personal favorites of mine, Eyes Without a Face and Peeping Tom,1 came out in 1960. Often, though, these elements were couched inside of films by well known directors or found in foreign arthouse releases like Onibaba or Kwaidan. Horror films were an afterthought to studio executives and so they never received the budget or the talent needed to make a great picture and back it with marketing. Instead, they were silly movies about monsters coming to take over the earth, full of hokey writing and over-the-top acting. They were made for teenagers looking for cheap thrills. The studios didn’t give George Romero money or talent either, which makes his achievement that much more remarkable. So while the legacy of Night of the Living Dead includes the obvious—the zombies that were defined in this film are pervasive in pop culture today—it also helped break new ground for horror as a genre, paving the way for classic films of the ‘70s and ‘80s like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and Alien.

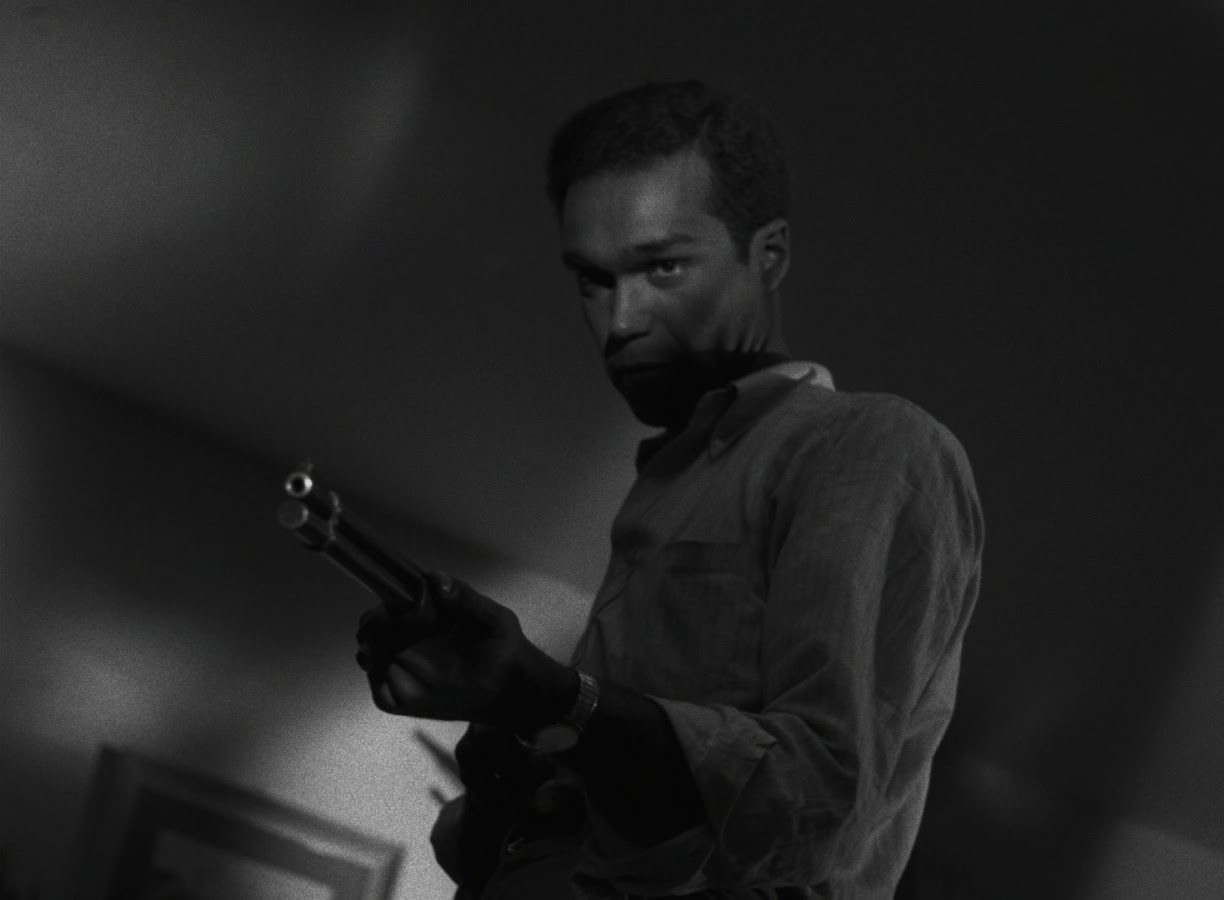

Night of the Living Dead is a wonderful hybrid, one that captures the brutality and despair of the meticulously crafted prestige films but features many schlocky B-movie elements as well. Adolescents stumbled into theaters with their dates, popcorn in one hand and Coca-cola in the other, expecting some laughs and perverse glee. Instead, they were assaulted by consistently horrific images—nude zombies, decaying flesh, the consumption of intestines, cold-blooded murder, a young girl gnawing on her dead father’s arm. The protagonists’ efforts, typically rewarded according to cinematic convention, continually come up short. Some people will say, “Everyone dies at the end,” if they want to jokingly spoil a film for someone. But in this case it’s true; our protagonist, the mild-mannered Ben (Duane Jones), seems to survive the all-night onslaught only to meet his demise at the hands of a clean-up crew who thinks he is one of the undead. A modern version of this traumatic experience would be going into a theater expecting something like Monsters, Inc. and being presented with Saw.2

After seeing Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s Tales of Hoffman as a youngster, George Romero became interested in film. He made short projects on a borrowed camera then enrolled at Carnegie-Mellon, majoring in theater and design. He formed a company with some friends and began shooting television commercials, but soon resolved to become a feature filmmaker. Focusing on the public’s desire for pulse-raising scares and noting the relatively low budget required to put together a horror film, Romero and co. set about writing screenplay drafts, moving from an initial idea of crash-landed aliens to flesh-eating ghouls.

The film’s opening scene immediately sets it apart from the hokey horror outings of decades past, as Johnny (Russell Streiner) mocks his sister Barbara (Judith O’Dea) about her fear of the graveyard. They’re visiting the cemetery to deposit flowers on their father’s grave, and the place has given Barbara the creeps since she was a child. But this is not a spooky graveyard at all; in fact, the scene takes place in broad daylight. There are no cobwebs, cawing ravens, or wolves howling at the moon. “They’re coming to get you, Barbara,” Johnny says with a smile, his silly vocal affectation giving a tip of the hat to all those silly old films. A man slowly approaches the siblings as Johnny continues to tease. Then, all in a blur, Barbara is assaulted, Johnny has his head thunked against a gravestone, and Barbara is fleeing in the car. Her jittery nerves cause her to crash it against a tree so she runs on foot to an abandoned farmhouse where she hides from the assailant. This is remarkably different in tone than the horror films of yesteryear.

Heightening the terror even more is the fact that Romero thinks through his film practically. The only thing different about this film and real life is that there happen to be walking, flesh-eating corpses on the loose. Otherwise, these characters must abide by the laws of reality. Windows must be boarded, the gas tank must be unlocked, food must be accounted for, and the encroaching undead army must occasionally be warded off by fire.

Soon after Barbara arrives at the farmhouse, we are introduced to Ben, who takes over as the main character. For the rest of the film, Barbara speaks only seldomly, consumed by hysteria induced by the apparent death of her brother. Two couples and a child are later found boarded up in the basement hoping to wait out the episode, and the parties begin butting heads as they figure out how to best deal with the situation. Reports from the authorities come via radio, and later, television. Several failed attempts are made at escape, and eventually Ben finds himself alone in the boarded up basement, a veritable army swarming above his head.

The creativity pulsing through Night of the Living Dead is palpable, from the black-and-white film (color was the norm at the time) which allowed the use of shaped-wax zombie wounds and chocolate syrup for blood, to the improvised lines from the cast members based on impressions rather than memorized dialogue. Jones in particular is responsible for much of the film’s character, completely changing Ben from an ignorant truck driver to an educated man. Jones himself was a learned fellow—multilingual, went on to head university departments and develop curriculum for the Peace Corps—and played his character that way. There are many different ways one could “read” Night of the Living Dead; you could look at the film as a critique of capitalism, religious extremism, the military, the government, the media, and on and on. But that all depends on the viewer. The only one that can’t be explained away as coincidence is the casting of Duane Jones as the lead character. In the middle of the civil rights movement, casting a black man as the lead in a film was enough to raise eyebrows. Having him punch a white woman in the face and plug a white man with a bullet was next level.3 Of course, we are subverting every expectation here, so although Ben is the only character to survive through the night, he gets headshot by a trigger-happy country boy the next morning, an ending that Jones thought would have a greater impact on viewers than his character surviving.

Considering the film’s title, without the years of legend built up around it, it seems like Night of the Living Dead is supposed to be a B-movie like those that came before it. But with its terrifying imagery, engaging camerawork, and vague, bring-your-own-social-commentary narrative, it becomes something much more than a mere horror movie. It kickstarted a cultural phenomenon that is still going to this day.

1. Michael Powell paid dearly for making Peeping Tom. The film was censored and many critics were calling for his head on a pike. Today it’s considered one of the greatest horror films of all time.

2. Even now, in the Year of Our Lord 2020, my wife misjudged how scary a movie from 1968 could be. We had trouble getting to sleep that night. But not, she will interject, because of the gore—she covered her eyes when the zombies were slurping meat off the femurs of the former survivors. She was upset by the convention-shrugging coda, in which Romero tears the rug out from under the viewer when Ben gets slugged in the head from afar by an ace rifleman. “But he’s the main character! I thought you said there were sequels!”

3. It was only the year before that Sidney Poitier slapped a white man in In the Heat of the Night.

Sources:

Gilligan, Matt. “8 Interesting Facts About George A. Romero’s ‘Night of the Living Dead’”. Did You Know?.

Fraser, C. Gerald. “Duane L. Jones, 51, Actor and Director Of Stage Works, Dies”. The New York Times. 28 July 1988.