“My family’s always been in meat.”

It seems like it should be impossible to say that a newbie director could haul a van full of unknown actors out into the blistering Texas summer, shoot some footage of them scrambling around a rickety old farmhouse, and cobble that together into one of the most viscerally terrifying films ever made. But that’s basically what Tobe Hooper did in the early 1970s. Sometimes ingenuity butting up against the limits of budget produces impeccable results in horror cinema (Night of the Living Dead, The Blair Witch Project, Paranormal Activity) and Hooper’s genre classic is an early example. With extremely modest funding, a large man with a scary mask and a chainsaw, and a hodgepodge collection of practical effects, the cultural phenomenon known as The Texas Chainsaw Massacre was born. Its legion of fans has been steady over the years as a slew of sequels and imitators have appeared in its wake, keeping the film’s title (if not much else) in the public consciousness. But the immediate shock of meeting Leatherface and co. for the first time is a tough act to top.

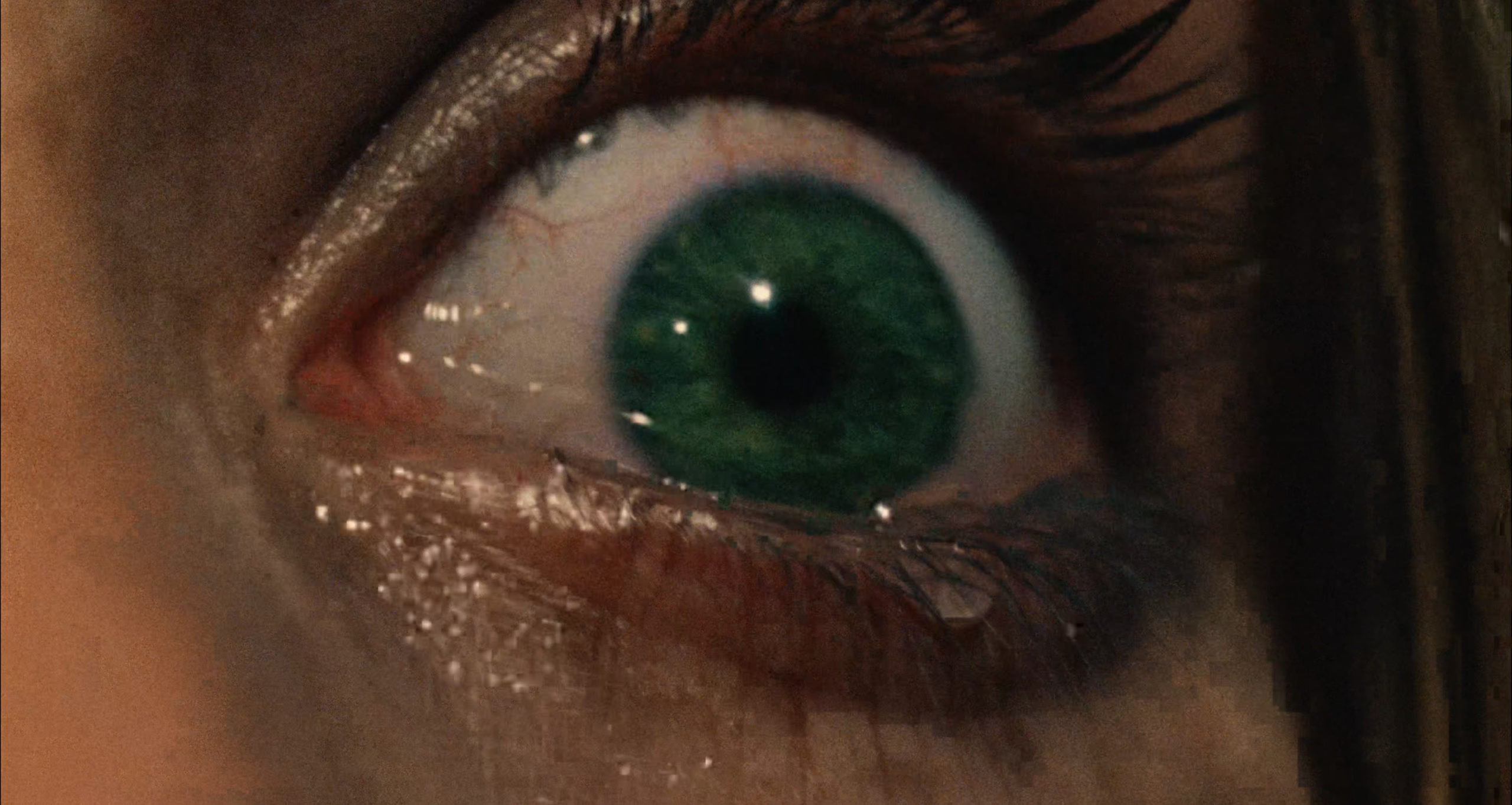

I vividly remember my first exposure to the grisly aesthetic of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. It was in a horror-comedy film class in college, which I took only with hesitation because it was a genre I knew little about at the time. We were discussing the trend of these long-running horror franchises to break into the popular consciousness with a gritty and visceral debut before shifting to a campier, self-parodic tone in subsequent efforts. To illustrate the transition, we obviously had to glimpse the before as well as the after. And so the professor threw the famous dinner scene up on the projector screen for us. I’ve never forgotten Leatherface, the Hitchhiker, and the Cook entertaining themselves by encouraging the near-dead Grandpa Sawyer to conk the gagged and bound Sally over the head with a hammer—a tin bucket waiting underneath her to catch the mess. Sally’s bulging eyes, the fillings in her molars, her whimpers—all are captured in immediate close-up as the trio giddily dance about, their whooping and hollering mingling with Sally’s muffled screams in a terrible cacophony. It’s terrifying stuff even if (like myself at the time) you haven’t seen what Leatherface has done to Sally’s friends over the past half an hour.

The plot of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is about as bare bones as you can get—something I usually only go for in more abstract or philosophically-minded films, but which works very well here. Sally (Marilyn Burns) and her paraplegic brother Franklin (Paul Partain) wish to visit the resting place of their grandfather after news has spread that someone has been vandalizing and robbing graves. Three of their friends, Kirk (William Vail), Jerry (Allen Danziger), and Pam (Teri McMinn), come with them. We briefly meet The Hitchhiker (Edwin Neal) who cuts open his own palm, disgusts his company with talk of head cheese, sledgehammers, and slaughterhouses, then slices at Franklin before being booted out of the van. When the crew stops to fill up on gas and find that the proprietor is fresh out, they decide to spend some time at their abandoned childhood home until the fuel delivery arrives. Kirk and Pam soon find themselves searching for an old swimming hole and stumble across a neighboring house.

We all know what’s coming, but our first glimpse of Leatherface (Gunnar Hansen) and his mask of human skin remains an iconic moment of grindhouse cinema. Kirk, hesitantly letting himself in through the open screen door, glimpses a wall decorated with dozens of taxidermized animal heads. He heads in the direction of some squealing animal noises and momentarily trips over a little transition ramp on the floor. Into the doorway steps the massive form of Leatherface (Hansen was 6’4” 300 lbs with size 14 feet), a hammer raised above his head. He’s on screen less than five seconds before he takes his first victim. It’s brutal in its nonchalant depiction of death, as Kirk convulses on the ground for a few seconds before Leatherface picks him up and slams the door shut. Kirk hasn’t even been inside long enough for Pam to worry about him. Once she does, her fate is much worse—not only does she get to watch Leatherface go at Kirk with his chainsaw, she gets to do so while suspended from a meat hook.

Quite a bit more happens between that stomach-churning sequence and Sally’s screaming/laughing getaway in the back of a passerby’s truck. Jerry searches for the others and finds Pam in a chest freezer before he meets his own fate at the hands of Leatherface. Franklin meets the chainsaw. Sally encounters the decomposing corpse of Grandpa Sawyer (John Dugan)—later nursed back to health on her own blood—and jumps out of a second story window. In a false moment of reprieve, we are introduced to The Old Man (Jim Siedow), who gags and ties Sally up and brings her back to the house, where we discover that The Hitchhiker is also part of this sadistic family. Then we’re at the dinner scene I discussed earlier.

That edge of your seat, teeth gritting intensity remains firmly in place from the moment of Leatherface’s first appearance. Even when the Sawyers are off screen, the environment that our protagonists find themselves in was designed with such a perfectly filthy aesthetic that you feel revulsion toward the place itself. I think that a large part of the gritty, authentic texture of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is an outgrowth of the grueling production. To keep equipment rental costs as low as possible, they shot sixteen hour days in triple digit weather. The house, which had no ventilation, was outfitted with furniture constructed from animal bones, latex made to look like human skin, chicken feathers, rotting meat, animal blood from a local slaughterhouse—look up some stills from the film, it’s an impressively repulsive set. The actors were required to use the same costumes throughout the shoot, and out of fear that Hansen’s face masks would lose their fearsome character if they were washed, he wore the same increasingly stinky mask1 for those weeks of long, hot days. Unintentionally, this smelly Hansen element provided a distance between him and the other cast members, which led to Leatherface’s victims experiencing some very authentic fear on screen—a fortuitous coincidence in hindsight.

![]()

Although Tobe Hooper frequently stated that his landmark horror film was “nearly bloodless” and deserved a PG rating—two claims that are emphatically not true—it is remarkable how much of the terror that The Texas Chainsaw Massacre induces in the viewer is from actions that are implied rather than depicted. There is definitely less gore than standard horror fare, but with all of the glamour stripped away, even the violence that is implied is the kind that makes you squirm in your seat. Understandably, it often goes unmentioned how solid Hooper was at constructing a shot. Yes, the torturing and the chasing are hectic and rapidly edited to convey terror—that can be disorienting, but it serves its purpose flawlessly. But even before we get to that, Hooper and cinematographer Daniel Pearl were capturing some really solid footage of the cast and set. There is one shot in particular, in which the camera tracks underneath a swing and up to the house, that is often called out for its technical excellence. In other places, the film’s gritty, 16mm aesthetic gives it the feel of found footage before that genre was really a thing. Capturing the natural beauty of the rural landscapes, Hooper leans into our cultural understanding of pastoral rural America only to pervert it with images of dying animals, rickety old houses, abandoned gas stations, exhumed corpses, and rusted out machinery. In Hooper’s hands, the isolated backwoods psycho-killer becomes a threat that could be hiding in plain sight.

Equally as crucial and often overlooked is the film’s sound design. Watching the film on mute is enough to make you fear traveling into small town America, but Hooper and Wayne Bell’s industrial sludge soundtrack and effects mix also superbly evokes a sense of terror. There’s plenty of info floating around the web regarding Hooper’s creative production techniques, and I think his work on the sound of the film deserves more attention. There are also a handful of folk songs from local musicians that serve as false indicators of security and normalcy when they crop up diegetically in the film.

Divisive at the time of release, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre broke all sorts of filmmaking rules to varying effect and wrote a playbook for an entire genre that has only rarely matched its success. Leatherface has become a preeminent icon of horror and has served as the archetype for many silent, masked imitators (Michael Myers from Halloween, Jason from Friday the 13th). If you haven’t seen it, don’t be fooled into thinking that it won’t be scary because it’s old. That might have been true of films of the preceding decades, but this one is the real deal—macabre set design, a legendary character, and great directing from Hooper make it a seminal horror film. It was a daring achievement in its time, and remains a weird, harrowing experience that tops most of the lesser films that have tried to replicate its success.

1. Leatherface actually wears three masks. Since he’s basically incapable of speech, his masks and mannerisms are how he conveys his thoughts. He has a killing mask for, uh, killing, a feminine mask for domestic chores, and a smiling mask for when he’s happy.