“You are making big profits from my work, my risk, my sweat. But that is okay, because I elected to make that deal. But now the deal is over. I want my end, and I am out.”

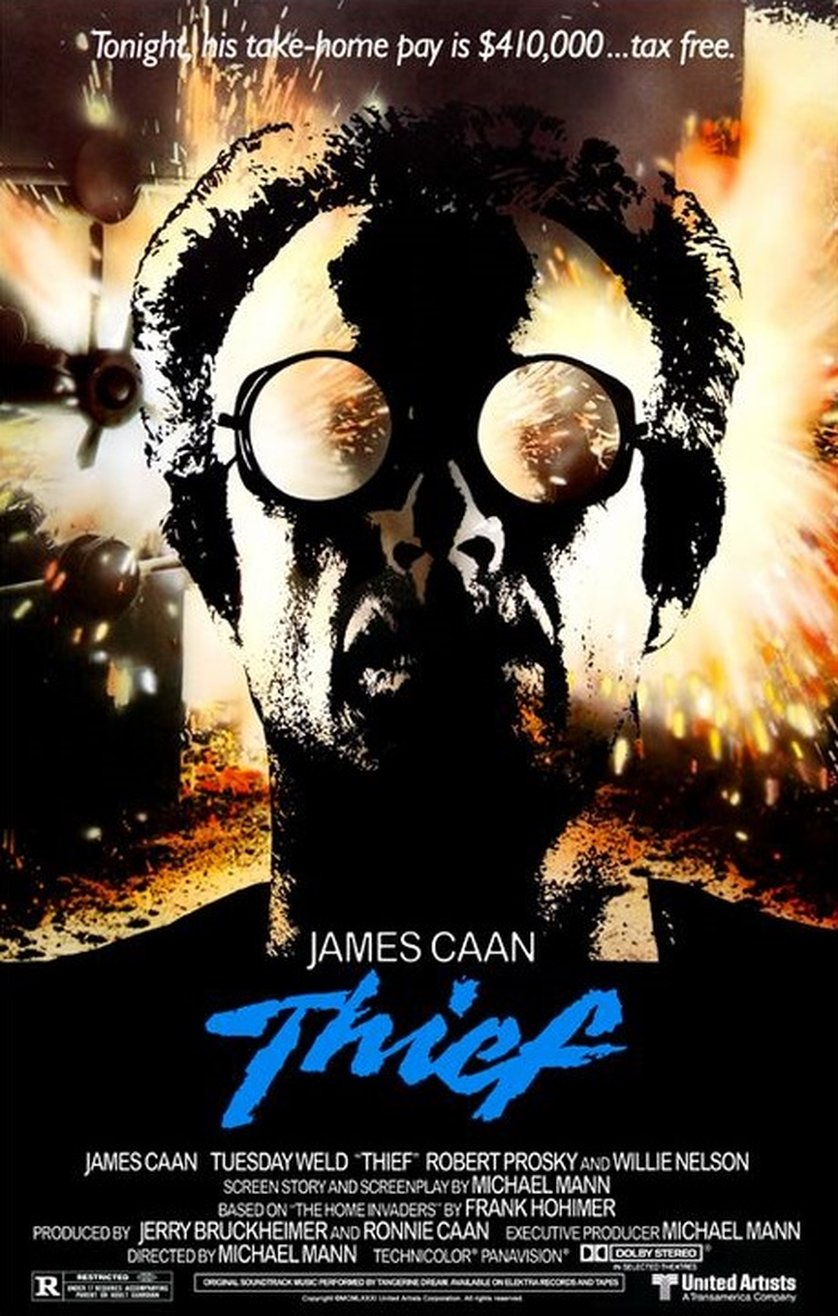

Matching the gritty auteurism that emerged in the ‘70s with the slick aesthetics that would mark the ‘80s, Michael Mann’s debut feature, simply titled Thief, announced a major talent and established the themes and styles that the director would explore over the course of his career.

It stars James Caan as one of those existential criminals in the mold of Alain Delon’s independent hitman in Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samouraï. Raised in the unnurturing environment of a state-run orphanage and formed by the harsh realities of a decade-plus stint in the state pen, Frank (Caan) is a blunt, antisocial man whose existence has been reduced to a primal state of survival.

He operates a used car dealership and a small bar in Chicago, both fronts for his efficient criminal enterprise. Though he’s mastered the art of thievery—a trade he learned behind bars from the freewheeling Okla (Willie Nelson, who looks like an old man in this film even though he’s still a touring musician in the Year of Our Lord 2022)—he yearns to ditch the criminal lifestyle and start a family, a dream that he’s hazily illustrated with a crude photo collage made from magazine clippings and photographs that he carries around with him. In service of this ambition, he’s arranged one last job that’ll earn him enough to make a fresh start and leave his old life behind him. Of course, starting over isn’t as simple as it seems, as the same things Frank desires—namely a house, a wife, and a baby—are the very things that ruthless mobsters can use to control people like him.

The film opens on Frank and his small crew, including his sidekick Barry (Jim Belushi), hitting a small safe tucked in the backroom of a local business—a low key job that they can pull off without catching any unwanted attention. But before Frank gets his cut, his fence, a bald, bespectacled fellow named Gags (Hal Frank), is murdered for cheating the mob. Frank pursues his money, barking and threatening his way up the food chain to the boss of the Windy City’s largest syndicate, a ruthless man named Leo (Robert Prosky), who, it turns out, has long admired Frank’s work from afar. He offers Frank a lucrative gig, a diamond heist that would bank enough cash to let him walk away for good. Frank’s initially reluctant, uncertain about cooperating with corrupt police officers, wary of the heat such a score might bring, and distrustful of Leo himself.

But where Frank sees himself as a lone wolf type, unperturbable, holding the world at arms length, we see him for what he really is: a lonely soul in need of human connection, his aggression barely masking his vulnerability. To wit, he decides, seemingly on a whim, to fall head-over-heels in love with a friendly cashier named Jessie (Tuesday Weld) who has said good morning and smiled at him on occasion. In one of the film’s best scenes, he sits across from her in an all-night diner and desperately lays out his homespun philosophy of life. He tells her about his institutional upbringing and his time in prison, about how the only way he made it through was to convince himself that he had nothing to lose and then act like it. But now he does want something to lose—specifically, he wants her. He wants a family. Jessie, who is essentially a stranger to Frank at this point, struggles to process his wild spiel as he delivers it, but pressed for an answer, she agrees to toss away her old life and throw in with him. And so Frank enters into a contentious arrangement with Leo, the thief intending to perform a single job, the boss aiming to bring a slick operator into his fold on a permanent basis.

While the plot of Thief is reliant on a number of tropes and coalesces into a final act as replete with double crosses and gunfire as you’d expect, it transcends its basic outline by presenting characters with depth, that feel lived-in and timeworn. There is violence, for sure, and the heist sequences are expertly realized—tense, meticulous, and technically sophisticated, providing the audience with a real sense of the process. But the bulk of the film’s screenplay involves characters conversing George V. Higgins-style in diners, offices, nightclubs, adoption agencies, parking lots; an achievement of character that is only possible because all of the principals are well cast. From Caan’s high strung misfit, to Weld’s world-weary cashier, to Prosky’s sadistic mob boss, to Nelson’s terminally ill cowboy, even the bit parts of beat cops and henchmen, the characters of Thief are all plausible individuals with loose ends and vague concerns and personal troubles that they’ve carried with them since long before the film began. The authenticity of the cast is enhanced by Mann’s casting of a number of ex-cons and police officers and the extensive interviewing of Folsom Prison inmates when he had shot the made-for-TV The Jericho Mile.

And yet despite that commitment to authenticity, Thief exists in a world not quite our own, as if Mann felt his efforts toward realism in scripting gave him license to make his film as aesthetically unreal as possible. Reflective surfaces—panes of glass, car hoods, rain-drenched streets—are all over the place, as are a colorful assortment of lights to illuminate them and a glistening synth score from Tangerine Dream to further detach the film from reality (although, it must be said, a mid-film performance of Mighty Joe Young’s ‘Turning Point’ is also a nice touch).

Ultimately, it’s this marriage of gritty, lived-in characterizations with the highly stylized nighttime wasteland that makes Thief such a compelling film. The bold neon lights and endless shadows serve as perfect atmospheric backdrop for Mann’s gestures toward sentimentality and his talkative script. I don’t think it’s such a crime that Mann’s career has largely consisted of making variations on his debut.