“Do you always have to go so far on principle, Vincent, or does it just come naturally?”

Many cite 1992’s The Player as Robert Altman’s return to form after a decade of small-scale obscurity (though I’d argue that his ‘80s run had a few notable high points; I’m particularly fond of Fool for Love). And while it may be true that The Player was the first time he had employed his old methods—large casts, expansive sets, overlapping dialogue—in quite a while, it was actually the previous year’s considerably less flashy Vincent & Theo, with its protracted story and bevy of striking locations, that saw Altman reclaim his status as a viable commercial filmmaker.

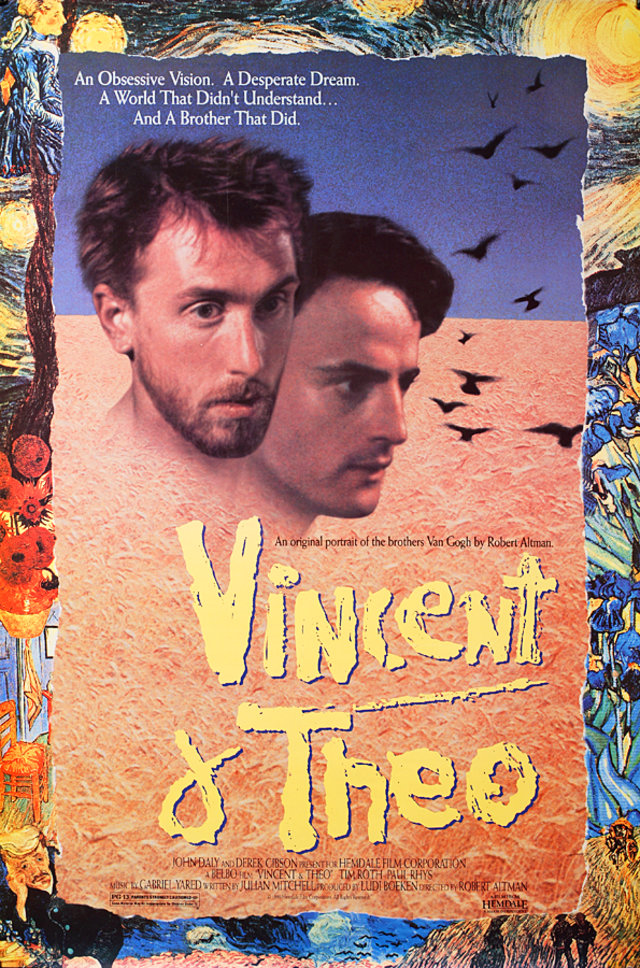

Whittled down from a four-hour television miniseries for theatrical release, with the edit overseen by the director himself, Vincent & Theo uses the biographical details of the lives of brothers Vincent (Tim Roth) and Theo van Gogh (Paul Rhys) to examine the inherent tension that develops in an artist whose passionate creative pursuits fail to generate a livelihood. It also covers themes of tortured genius and the inexhaustible bond between brothers.

Vincent van Gogh’s life has been reconstituted in popular media numerous times—most notably Vincente Minnelli’s Lust for Life—and Altman covers the familiar beats, from his bold decision to commit himself to painting, through to his death by his own hand less than a decade later. The film captures the severe lows and euphoric highs that stem from the painter’s bohemian way of life, presenting a hideously flawed, existentially-haunted, manic depressive crippled by his passions and self-hatred, without poeticizing the realities of his situation. Less familiar is the story of younger brother Theo, a high-strung art gallery manager who loathes that the outsider art he appreciates is not commercially viable. He graciously shares his meager income to subsidize his basically parasitic brother’s career, perhaps envious of the artist’s purity of purpose.

The brothers’ symbiotic relationship gradually emerges from a smart screenplay by Julian Mitchell that first develops their stories in tandem by aligning life-altering events for maximum dramatic heft. Indistinctly demarcated vignettes play out over the course of years, with sequences bleeding into one another as if being recollected in a jumble from some point in the future. By the time they are nearing the end of their lives (Theo succumbed to syphilis only a few months after Vincent died), the brothers have become so interdependent and so religiously dedicated to their art that little else matters to them beyond their capacity to transform the mundane into the beautiful.

Altman is much less interested in tribute (or even a proper biography) than in commiserating with those interior conflicts, so while he includes the expected biographical elements—his contentious relationship with a prostitute (Jip Wijngaarden), his friendly rivalry with Paul Gauguin (Wladimir Yordanoff), the mutilation of his ear, his hatred of Christianity, his care at the hands of Paul Gachet (Jean-Pierre Cassel), his suicide—these major story elements are no more important to his aims than establishing Theo’s fraught marriage to Johanna Bonger (Johanna ter Steege) or his contentious relationship to his affluent clientele. Perhaps the most insightful moment comes when Vincent, standing in a field of sunflowers that were his subject, destroys his canvas out of frustration. Jean Lépine’s camera bobs and weaves, inspiring the sunflowers themselves to become a hostile audience. This contrasts with the film’s opening sequence, which overlays archival videotape from a 1987 auction where van Gogh’s “Vase with Fifteen Sunflowers” sold for a record-breaking amount, with the man himself, more than a hundred years prior, living in squalor.

The irony of the initial scene is transparently obvious, and yet as the auctioneer continues to drone on we realize a subtle additional insight: the vast difference between the monetary value of a van Gogh painting then vs. now is not quite as astonishing as the gulf between the harsh personal reception then vs. the reverential treatment now. By the film’s end, the dollars and cents side of things has faded to the background, the focus trending toward the bleak realities of obsessive commitment to one’s craft at the expense of all else in life. Of course, one can’t help but notice the parallels between van Gogh’s commercial struggles and Altman’s uneasy relationship with Hollywood. Indeed, it’s probably that very connection that drew the filmmaker to the project in the first place.

Though I can’t imagine watching a four-hour cut of Vincent & Theo, the theatrical version that’s in circulation is a fine picture marked by a forceful performance from Roth, resplendent production design from Stephen Altman, a provocative score from Gabriel Yared, and a perceptive, harrowing examination of the creative process.