“This town… I really think it’s like something out of the Bible.”

“What part of the Bible?”

“The part right before God gets angry.”

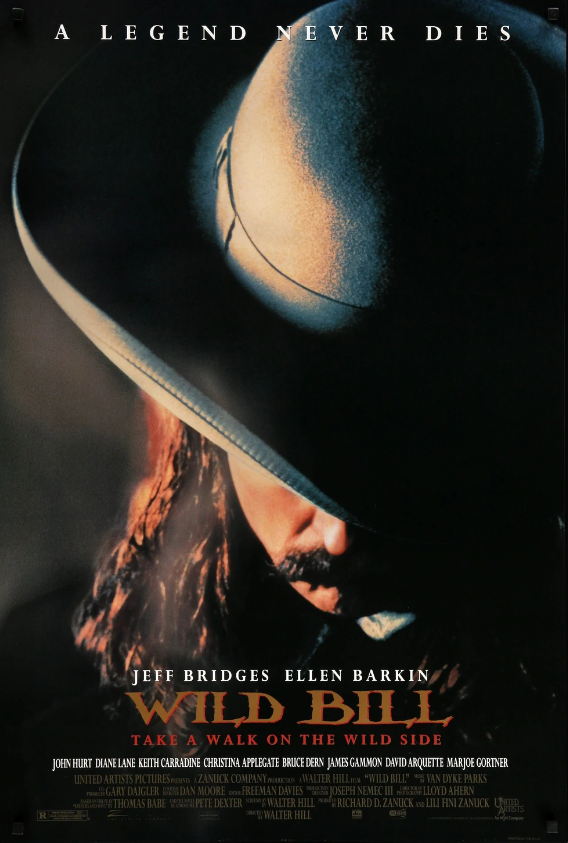

There’s a sequence toward the end of Walter Hill’s Wild Bill where Jeff Bridges’ ailing icon ambles along the main street of Deadwood. John Hurt’s Charley Prince, a British dandy turned cowboy who has narrated the film throughout, informs us that “The theater of Bill’s life had come to demand that he walk up the center of a muddy street rather than use the boardwalk. He had discovered being Wild Bill was a profession in its own right.”

It’s this central question of separating the man from the legend that not only informs Hill’s kaleidoscopic biopic, but haunts its central subject as well. Indeed, the James Butler Hickock of Wild Bill is less a mythic figure than a man scared of his own mortality and tormented by a nascent conscience, actively fleeing an outsized persona that has taken on a life of its own. Like the members of the James-Younger gang that Hill examined in The Long Riders, Bill has lived long enough to see his personal history elevated into folklore and exaggerated beyond comprehension. His hyperbolic mythos has preceded him to each and every borderland town, preemptively securing his reputation and preventing any social escape or moral reprieve for the aging recalcitrant. And so he wanders the frontier with abandon, perpetually hungover and brooding, miserably playacting as the gunslinger he no longer wishes to be but too stuck in his ways to change them.

Breathlessly paced, wildly uneven, and marked by B movie action, the film quickly establishes Bill Hickock as a man of violence and wit with a series of grisly vignettes that hinges around his accidental killing of a deputy while serving as a U.S. Marshal. After a brief tenure at Buffalo Bill’s (Keith Carradine) Wild West show, a glaucoma diagnosis, and duel with a crippled old man (Bruce Dern), he stumbles into Deadwood, aging and regretful but still vain and unapologetic, where he meets a fidgety young transient (David Arqueete) with a vendetta against him.

The film settles down a little bit once we reach the fabled frontier town, but even here the “main” narrative is riddled with hazy black-and-white sequences that are either flashbacks, drug-fueled fever dreams, or some combination of both. In this way, we are pulled into Bill’s fragmented reality, where fact and fiction have been hopelessly entangled and the myth now reigns supreme. Within this murky milieu, we bear witness to Wild Bill’s last few days on earth, which he spends drinking, consuming opium, playing cards, lashing out at those who care for him, and ruminating on his course of life.

Though Wild Bill bears many similarities to The Long Riders—which highlights the brief reign of the James-Younger gang—the films differ in one critical aspect. Whereas the earlier film is fashioned after works of Sam Peckinpah, the later takes its cue from Altman’s Buffalo Bill and the Indians. That is to say, rather than anti-heroes, mystique, and narrative clarity, Wild Bill is marked by a critical deconstruction of a historical-mythological figure and a story that is fragmented and obtuse. Many of Hill’s creative energies are explicitly directed toward this aim—his unromantic depiction of the character, his claustrophobic cinematography (from Lloyd Ahern II), the languid and perplexing interludes, the rain, mud, and perpetual dusk. It almost becomes oppressive, just as Wild Bill’s runaway self-constructed mythology has become oppressive.

You can typically rely on Hill’s work to look interesting, move along at a steady pace, and feature solid performances. All of these are true of Wild Bill. The Deadwood set is a filthy cesspool, the visual textures are varied and arresting, the period score from Van Dyke Parks is malleable and complementary, the action is well executed, and Bridges embodies Hill’s vision of the iconic character: a stony-eyed force of nature with a larger-than-life charisma, simultaneously proud of his reputation and plagued by doubts. Several of the minor parts are superbly realized as well, among them James Gammon’s California Joe, Marjoe Gortner’s preacher (but of course), the aforementioned roles for Dern and Carradine1, Diane Lane as one of Bill’s old lovers, Christina Applegate as a prostitute, James Remar and Stoney Jackson as hired gunmen, Karen Huie as the proprietor of an opium den. The other main players—John Hurt’s friendly bystander, Ellen Barkin’s Calamity Jane, and David Arquette’s cartoonish Jack McCall—never quite rise to Bridges’ level, but they do not actively detract from the film.

The film waivers a little bit as it searches for the correct tone. By turns comical, contemplative, psychedelic, and action-packed, it occasionally suffers under the weight of its own grand ambitions. Sometimes it appears as if Hill isn’t quite sure how to play certain scenes or how to tack his disparate aims onto a shaky revenge narrative (a fictitious tale created for the film because the reality is less exciting). It recovers from most of these momentary stumbles, but if one of its elements doesn’t work for you—most likely the hallucinogenic dream sequences—it likely won’t work as a whole. And, if you prefer your Westerns to uphold their mythological heritage, you’ll be put off entirely. In any case, the stitched-up non-chronological film is undeniably a shaggy beast that is difficult to get a firm handle on.

1. Carradine would take on the role of Wild Bill less than a decade later in David Milch’s Deadwood television series. If Wild Bill doesn’t exactly sit alongside the best of Hill’s other work, it at least serves as a nice companion piece to Milch’s impeccable show, on which Hill served as a consultant and directed the pilot episode.