“There’s something on this station. Something you wouldn’t believe.”

The Alien franchise has never translated well to the medium of video games. Almost all of the twenty-something-odd officially licensed games attempt to fit into the shooter genre, which simply does not match the spirit of the original film. To be fair, most of the modern games take their cues from Jame Cameron’s Aliens, which is a much more trigger-happy affair than Ridley Scott’s 1979 Alien. Case in point is Gearbox’s Aliens: Colonial Marines, which has the player mowing through Xenomorphs like they’re run of the mill baddies. But that’s not what the original Alien was about. Not at all. That film had one single enemy. Think of the fear engendered by that seldom-seen creature, and of Ripley cleverly defending herself with limited resources. That’s a completely different dynamic than a machine-gun toting space marine mowing down legions of Xenomorphs. Alien: Isolation, developed by Creative Assembly, is a love letter to the original film, pitting the player against an expertly designed AI alien that is unpredictable and menacing. Oh, and you can’t kill it. The game perfectly captures the dread of being trapped aboard a spaceship with the eight foot tall creature. Now, it’s not always fun. There are many unforgiving sections of the game, and the save system does not lend itself to casual play. It may cause more anxiety than gratification, and unlike the film, it’s not a matter of simply waiting it out or covering your eyes until the scary part is over. You’ve got to play your way through it; you’ve got to choose when it is safe to peek out of your hiding place, when to throw a distractive flare, when to loudly sprint to a vent vs. silently crawl. If you mess up—as you will countless times—you’ll find the pointed tale of the Xenomorph protruding through your abdomen, or its mouth-within-a-mouth ramming its spiked teeth into your face. It’s not for the faint of heart, but it’s undeniably the closest a licensed game has come to matching the style and tone of the first film in the franchise.

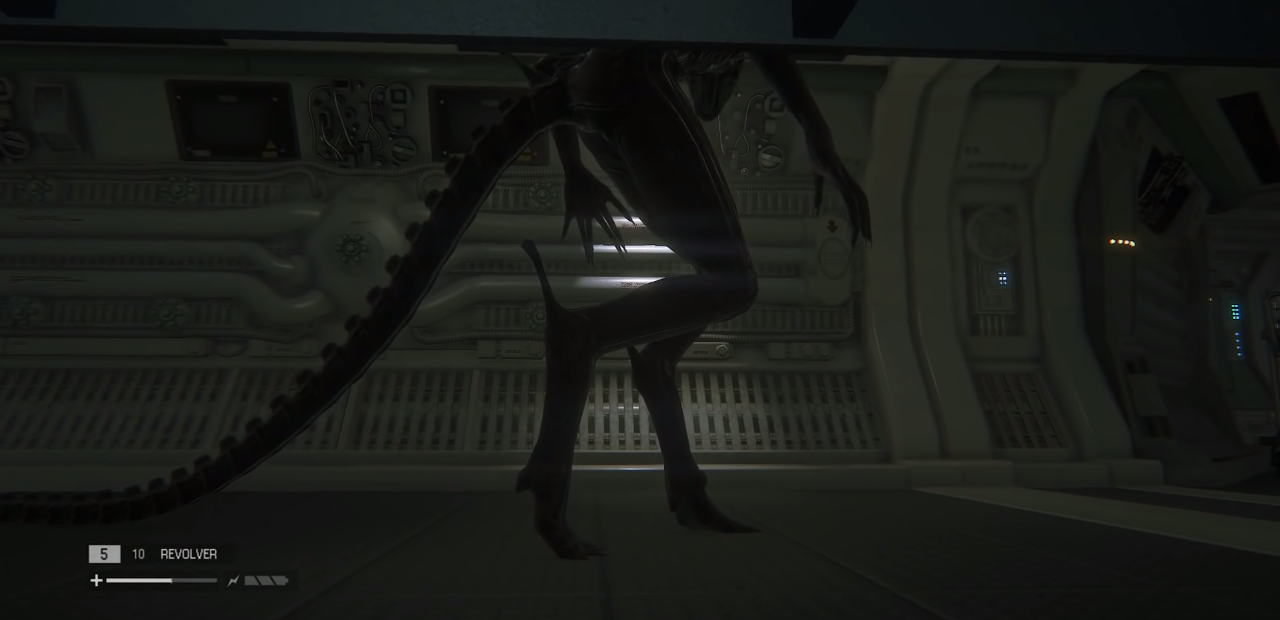

You’re given a maintenance jack to loosen nuts and beat human enemies to a pulp, as well as the ability to craft some distractive devices such as noisemakers, smoke bombs, and flares. You’ll eventually have the use of a revolver, a shotgun, a flamethrower, and a bolt gun too. Save the flamethrower, most of what you use is hardly effective against the Xenomorph. In fact, making any loud noise at all will attract the creature to your exact location, in which case the flamethrower is your only real defense besides elusion. And it’s not just noise that attracts the alien. Sure, if you sprint, it’ll be there in a few seconds to investigate the source of the noise. But many times it will survey an area for minutes at a time without any discernible reason, causing the player to cower beneath a desk or remain tucked inside of a cabinet for minutes on end as it sniffs around looking for you.

Several unique elements serve to increase the tension. Many objectives require accessing computers or utilities interfaces that bleep and bloop. Same with the phones that act as save stations and the access tuner that allows you to unlock doors and hack terminals. As soon as you engage with a piece of equipment—which again, makes noise—you are locked into that action for at least a handful of seconds. If the alien is nearby, there’s a chance you’ll be gutted as you frantically rip through the contents of the computer or helplessly wait for the save screen to stop the flow of time. Another way the developers keep the game tense is that your revolver and shotgun must be reloaded one round at a time. This works less well, since you only use your weapons against enemies that are not the alien—like I said, the guns don’t work on the alien—but these enemies can mostly be avoided without firing a shot anyway.

There are a few scripted moments where the alien must show up—and these are freaking fantastic, as far as scripted, non-cutscene moments go—but the real terror comes from the smartly designed AI that makes the creature’s movements hard to predict. You’ll often find yourself cautiously emerging from your hiding spot after the alien has left the room, only for it to circle back around and impale you; or you’ll peak out and see that its spindly tail is still twitching in the doorway as the monster lurks just outside in the shadows. The first person perspective makes this even more tense as its not simply a matter of jockeying the camera angle from a third person view—you actually have to expose yourself if you want to get a better vantage point. The sound design does a lot of subtle work here as well. The chugging machinery and dull hum of Sevastopol’s innards routinely startle the player, even though no danger is near. Eventually, you will learn the telltale sounds of the alien—its heavy footsteps, its menacing rattle, the harsh thuds as it re-enters the vent system through the ceiling.

On the harder difficulty settings, the alien is a constant threat, which means, if you don’t have the correct temperament, your experience could be reduced to a few hours of hesitantly peering through the slits of a locker door before you give up on the game. You must force yourself to press forward. Although I’m not 100% sure if it is automatic or based on your previous actions, it seems that the alien becomes harder to fool as the game progresses. Instead of investigating your noisemaker, it will search the area the noisemaker was thrown from. This is a remarkably immersive experience—one that some clever hackers have enhanced by adapting it to VR—but not necessarily one that I would call “enjoyable.” It’s nerve-wracking and is liable to make the player mentally worn out rather than serve as the mental break that video games provide for many players.

![]()

The story is not a simple retelling of Alien, but rather a similar one told through the eyes of Ellen Ripley’s daughter, Amanda. As Amanda, the player will traverse the space station Sevastopol, an orbiting city that holds the flight recorder of the Nostromo, a potential avenue for closure regarding the fate of Ellen Ripley. But we soon find out that Sevastopol has been brought to ruin by a single alien creature lurking through its maze of vents, corridors, and bulky machinery. Yes, it’s completely preposterous that Amanda would go searching for her mother and end up in the exact same scenario. But even though it plays things safe and feels derivative, it fits neatly into the canon and provides enough wrinkles that it doesn’t feel completely stale. There’re a few twists and turns, but the highlights are the scenes in which Sigourney Weaver reprises her role as Ellen Ripley, an element which lends the game a sense of authenticity. Further bolstering its legitimacy is a commitment to the 1970s lo-fi vision of future tech, featuring vintage visual and aural aesthetics. The retro set design was lifted straight from the cinematic era, with coiled tubes, metal paneling, steaming vents, and fluorescent lighting giving the whole station a sheen of age and use. Analog audio tapes and monochrome computer screens upon which you can read personal emails of Sevastopol residents pull double duty by fleshing out the story and adding to the charm. “We had this rule: If a prop couldn’t have been made in ’79 with the things that they had around, then we wouldn’t make it either,” said artist John McKellan in an interview with GameFront.

With all the attention paid to the aesthetic design and the enemy AI, the game falls short in several other areas. The pacing suffers quite a bit, and after several shifts from alien encounters to android evasion, the game outstays its welcome via repetitive go-to-location-to-pull-lever missions. Several missions amount to little more than controlled cinematics with no threat at all; in which case, why not just show a cutscene? And for all its focus on being cinematic—a feat that it largely achieves, at least from the perspective of someone looking for the feeling of mounting dread from the film—its characters mostly fall flat, with the humanoid robot Samuels having the most emotional line of the entire game.

Although the superb alien AI and the wonderful visual and aural design are not enough to sustain the game for its entire runtime, they are enough to make Alien: Isolation a legitimately great horror game. There are not many comparable experiences to be found in the medium—there’s Outlast, where you evade homicidal psych ward patients without the use of weapons; or more standard survival horror fare like The Evil Within, Alone in the Dark, or Condemned: Criminal Origins—but none of these have the depth of the enemy AI found here, nor the retro aesthetics that make it such a stylistic standout. I haven’t played many of the other games that have cashed in on the legacy of the film franchise, but it would be silly to expect something better than this from a movie game.

Sources:

Hornshaw, Phil. “Alien: Isolation is ‘The “Alien” Game We’ve Always Wanted to Play”. GameFront. 7 January 2014.