“Sounds like a dream.”

“Just as long as I can keep from waking up.”

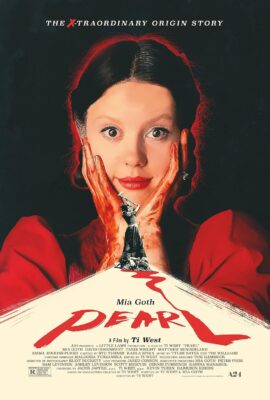

Without really meaning to, I’ve been blasting through a bunch of sequels lately. In virtually every case the sequel was an inevitability given the success of the original. Not so with Ti West’s Pearl—which is a prequel and so technically not the same as the other films mentioned, but whatever—a film conceived and greenlit during the making of X (2022) and shot right after the original production wrapped. Apparently West and starlet Mia Goth had so much fun cooking up a backstory for the nasty old hillbilly villain of the original that they couldn’t help but make a full-on feature documenting the traumas that shaped the woman’s life.

There’s a hint of parody as West works up a Sirkian melodrama in vivid faux-Technicolor, about the young Pearl (Goth) who dreams of being a movie star or stage dancer but is instead stuck toiling under the watchful eye of her strict mother (Tandi Wright) and caring for her invalid father (Matthew Sunderland) on the family farm during the Spanish flu pandemic. However, the distortion of the mid-century Disney aesthetic is not exaggeration but perversion, exemplified by the freshly butchered hog that sits on the front porch and is gradually overtaken by maggots. An early song and dance number where Pearl sings to her cow pals, for instance, is played pretty much straight. But then, just as giddily, she pitchforks a goose and feeds it to her pet alligator. She takes a dreamy trip into town, covering her face to ward off the plague, sneaking into the movie theater, and chatting with the suave projectionist (David Corenswet)—a terrible temptation since her husband Howard (Alistair Sewell) has gone off to fight in the Great War. It feels like a scene from a fairytale, then on the way home she dumps her bike and sidetracks into a cornfield where she seduces and makes love to a scarecrow. “I’m married!” she screams when she comes to her senses.

Indeed, one of the chief pleasures here is that the character that Pearl must become for her role in X precludes West from providing her with anything resembling a conventional origin story. The Pearl we’re familiar with is deeply unstable and perverted, only tenuously grasping reality. The goal is not to take an iconic villain and cast her as a misunderstood outsider worthy of some form of sympathy, but to take a mentally unsettled young gal and really mess her up. And circumstances are perfectly orchestrated to bring about this end. As her proper young lady façade falls away, we come to see a violent, vile, narcissistic personality emerge, one that’s probably been lying dormant beneath her mother’s overbearing control and that quaint farmgirl persona for years.

She thinks she deserves to be a star and the only thing standing in her way is her vegetable father and her repressive mother, so when the opportunity presents itself, she claims their lives. We know this is coming, of course, but West has dangled the carrot of escape with the glamorous projectionist and not yet snatched it away, and so we’re a little bit surprised by how quickly our guarded sympathy morphs into morbid fascination. And then the carrot is indeed snatched away and the projectionist meets the same fate as the goose and we must conclude that we’re not witnessing an origin story so much as an early episode in the life of an innately unhinged and evil person whose default state is disturbed, damaged, dangerous. Kind of like how Maxine begins and ends X by snorting cocaine and never becomes the archetypal final girl, Pearl is an antiheroine that we cheer on even though the narrative stars have not aligned for her violence to be justified, cathartic, or expedient. Her situation is dire, true. Her mother’s embrace of suffering is hard to stomach, true. Her only outlet is the movies, true. And those have now been perverted because Mr. Cool Guy Projectionist decided to show her a stag film.1 That things go off the rails is not surprising at all. But the simple fact of the matter is that Pearl is just not right in the head and her killing everyone she knows will solve none of her problems and is seemingly not motivated by the circumstances. After all, this is a woman who will, six decades hence, slay an entire group of young pornographers for making her jealous of their youth.

It all climaxes beautifully with a mesmerizing, protracted confession where a sliver of humanity peaks through and Pearl unloads her accumulated sins onto her sister-in-law (Emma Jenkins-Purro). It’s really quite complex and mesmerizing as all of Pearl’s accrued layers of artifice come to bear—the dreamer, the gentle housewife, the evil and base creature that believes it is the center of the universe, the monster pretending to be the gentle lady, the monster striving to be the gentle lady. This is all up there on Goth’s face throughout the film, but here she’s flailing around trying to articulate the madness inside her and it’s pretty devastating as those aspects of her persona vie for authority. Then—you guessed it—Pearl hacks the sister-in-law to death with an axe.

The film does lose some of its distinct flavor once Pearl starts going on her killing spree (until then you might not even call it horror; if it wasn’t set in 1918 but in modern times you’d probably just call it psychological thriller), but it retains throughout the unusual aesthetic and mood with which it begins, that sense that Jane Powell got teleported off the set of Seven Brides for Seven Brothers (1954) and dropped down on the set of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) and her Milly character is not a goody two-shoes but a demented serial killer. Which is, I believe, exactly the intended effect, although it’s much more challenging to make this feel naturally cohesive and artistically valid than it was to make a ‘70s exploitation film seem so with X, because ‘70s exploitation films are an actual thing that can be mimicked but there are not very many ‘50s melodrama horror films set during WWI and also because West is, based on the evidence, simply not as overwhelmingly in love with the era as he is with ‘70s and ‘80s horror. What he is also definitely in love with is Mia Goth’s face and I will not spoil the memorable final shot except to say that it features a lot of Mia Goth’s face.

1. West uses A Free Ride (1915), one of the first widely distributed pornographic films, which is, sadly, less pornographic than about half the mainstream films showing at your local theater on any given Tuesday.