“We translate every situation, every experience, into the same old codes. We just condition ourselves.”

“We’re creatures of habit. Is that what you mean?”

“Something like that.”

Maybe The Passenger is the best Antonioni film I’ve seen, or maybe I’ve just finally adjusted to his unique style of filmmaking, which is marked by gorgeous locations, elaborate mise en scène, careful compositions, banal flirtations with genre, sluggish pacing, and existentialist themes. Or maybe a restrained, and thus uncharacteristically uninhibited, Jack Nicholson is the ultimate X factor. Whatever the case, I found myself actually enjoying the film moment by moment as opposed to merely admiring, unpacking, and contemplating as I did with films like L’Avventura and Blow-Up.

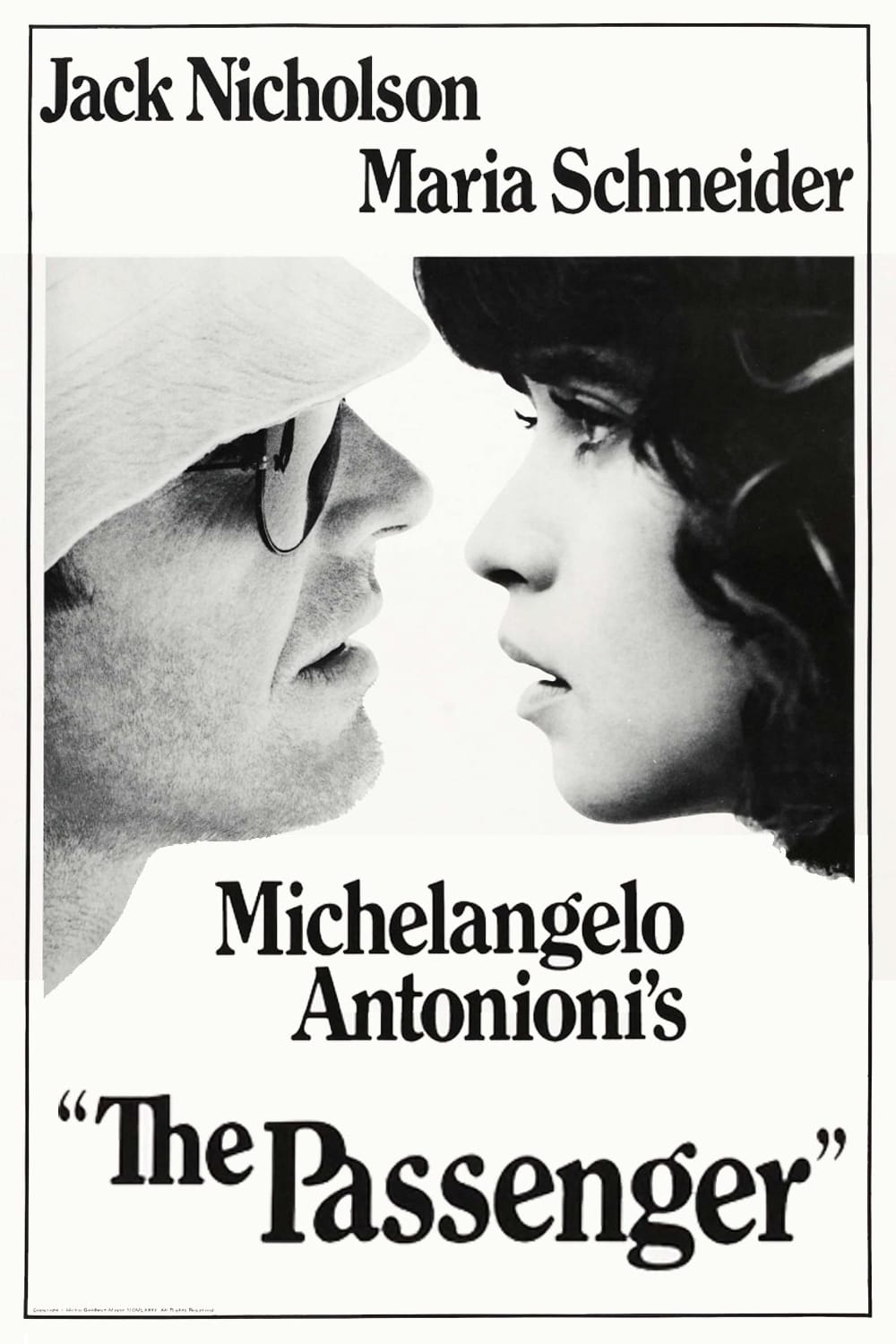

Set in the aftermath of the Vietnam War and the various social revolutions of the 1960s, the film documents one disillusioned man’s search for purpose and identity; the lone cynic standing in for the hyper-modern culture at large. Sent to Africa to cover the civil war in Chad, American reporter David Locke (Nicholson) struggles to find an objective journalistic angle (likely inspired by the ugly reception of Antonioni’s documentary Chung Kuo, Cina), stumbles around the Sahara Desert, and then wanders back to his one-star hotel where he finds that David Robertson (Charles Mulvehill), a new acquaintance and the only other Caucasian around, has died of natural causes while lounging in his room. Impulsively, Locke elects to switch identities with the dead man and leave his old life behind, quickly doctoring their passports and lugging the corpse into his own room so that David Locke will be officially deceased. He follows Robertson’s meeting schedule and soon finds himself faking his way through meetings with arms traffickers, evading a former colleague (Ian Hendry) that his “widow” (Jenny Runacre) sent to get in touch with Robertson, and going on the run with an enigmatic architectural student (Maria Schneider, fresh off her intense experience with Brando in Last Tango in Paris) he meets in Barcelona.

Like other Antonioni films, social and psychological structures in The Passenger are vague to the point of immateriality. Time, too, is protracted and indistinct. Most of the film consists of Nicholson listlessly ambling around various locales, with a guerilla leader’s covertly filmed execution serving as the only major disruption. Motivations are opaque, relationships incidental. All of these things underscore an apathetic worldview in which life and the universe have no coherent or discernable composition. No matter where Locke goes—Africa, Spain, Germany; the city, the countryside, every place pregnant with a sense of personal history, especially those buildings designed by Catalan architect Gaudí, whose life’s work, philosophy of art, and famous death provide the film with thematic heft—in whatever environment, he is plagued by a Humean skepticism of cause and effect.

If his thoughts and actions do not have predictable outcomes, how could they have predictable consequences? How can he hope to generate a consistent persona that would form the bedrock of his sense of self? What do relationships between people and between man and his environment look like from this cosmological vantage point? For Locke, and Antonioni, life itself is ultimately unintelligible—even if achingly beautiful on occasion (but what is beauty in this perspective?)—and thus the film is intentionally languid and uncertain in its narrative construction. Unlike Gaudí, who was utterly dedicated to his vision, Locke is a mere passenger, an observer, coasting on momentum, unwilling to commit and immerse himself in the living of his own life.

This pessimistic philosophy is nowhere more apparent than in the film’s famous penultimate shot,1 a creeping dirge that focuses more on the town’s architecture and geography and local color than on the narrative activity happening off screen, and which seems to owe some debt of inspiration to Michael Snow’s Wavelength (though the two oughtn’t be compared at much length). Appropriately, we don’t get to see the fate of the character with whom we’ve spent the last two hours, who finally realizes that his belief system will not allow him to establish a new narrative foundation for his life; will not allow him to outstrip his past. But he’s purchased a one-way ticket and takes a drastic measure to escape his spiritual agony.

1. To me, the earlier in-camera flashback sequence is equally intriguing as the lengthy shot that brings the film to a close.